Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)

| Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 12 September 1980 | |||

| Recorded | February–April 1980 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 45:37 | |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) | ||||

| ||||

Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps), also known simply as Scary Monsters,[a] is the fourteenth studio album by the English musician David Bowie, released on 12 September 1980 through RCA Records. His first album following the Berlin Trilogy (Low, "Heroes" and Lodger), Scary Monsters was Bowie's attempt to create a more commercial record after the trilogy proved successful artistically but less so commercially.

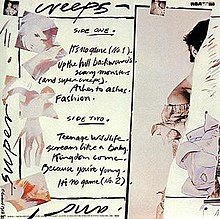

Co-produced by Tony Visconti, Scary Monsters was recorded between February and April 1980 at the Power Station in New York City, and later Good Earth Studios in London. Much of the same personnel from prior releases returned for the sessions, with additional guitar by Chuck Hammer and Robert Fripp, and a guest appearance by Pete Townshend. The music incorporates elements of art rock, new wave and post-punk. Unlike the improvisational nature of prior releases, Bowie spent time writing the music and lyrics; several were recorded under working titles and some contained reworked elements of earlier, unreleased songs. The album cover is a large-scale collage featuring Bowie donning a Pierrot costume, with references to his prior releases on the rear sleeve.

The album's lead single, "Ashes to Ashes", revisited the character of Major Tom from "Space Oddity" and was promoted with an inventive music video. Scary Monsters garnered critical and commercial acclaim: it topped the UK Albums Chart and restored Bowie's commercial standing in the US, reaching No. 12. Scary Monsters would later be referred to by commentators as Bowie's "last great album" and a benchmark for subsequent releases. It was Bowie's final studio album for RCA and the final collaboration between him and Visconti for over 20 years. Several publications have considered it one of the greatest albums of all time. The album has been reissued multiple times, and was remastered in 2017 as part of the A New Career in a New Town (1977–1982) box set.

Background

[edit]From 1976 to 1979, David Bowie recorded what became known as the Berlin Trilogy, which consisted of Low, "Heroes" (both 1977) and Lodger (1979), made in collaboration with the musician Brian Eno and the producer Tony Visconti. Although considered highly influential,[1] the trilogy had proven less successful commercially.[2] Lodger's commercial performance was hindered by artists who were influenced by the earlier Berlin releases, such as Gary Numan.[3] According to the biographer David Buckley, Numan's fame indirectly led to Bowie taking a more commercial direction for his next record.[4]

Recording

[edit]Recording for the album began at the Power Station in New York City in February 1980. Bowie informed returning producer Tony Visconti that this was going to be a more commercial record than his previous releases.[5][6] Eno did not return, having ended his collaboration with Bowie after Lodger, stating he felt the Berlin Trilogy had "petered out" by that record.[7] It would be the fifth and final Bowie album to feature the core lineup of Dennis Davis (drums), Carlos Alomar (guitar) and George Murray (bass), who had been together since Station to Station (1976); only Alomar would continue working with Bowie hereafter.[5]

King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp, who played on "Heroes", was brought back for the sessions, replacing Lodger guitarist Adrian Belew.[b] Bowie hired an additional guitarist, Chuck Hammer, after hearing him play with Lou Reed in London the year before.[5] According to the NME editors Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray, Hammer added multiple textural layers deploying guitar synth and Fripp brought back the same distinctive sound he lent "Heroes".[9] The pianist Roy Bittan, a member of Bruce Springsteen's E Street Band, returned from the Station to Station sessions.[c][5]

Initial sessions at the Power Station took place over two and a half weeks, with an additional week used for overdubs. Tracks completed were solely instrumental.[5] One instrumental, titled "Crystal Japan", was originally intended to be the album's closing track, but was dropped in favour of a reprise of "It's No Game";[d][11] the reprise, titled "It's No Game (No. 2)", was completed in its entirety during the initial sessions.[5] At Alomar's suggestion, Bowie recorded a cover of Tom Verlaine's "Kingdom Come". Bowie felt the track was a standout from Verlaine's 1979 eponymous solo album and asked Verlaine to play lead guitar. Verlaine agreed, although Fripp ended up playing lead guitar.[e][12]

There was a certain degree of optimism making [Scary Monsters] because I'd worked through some of my problems, I felt very positive about the future, and I think I just got down to writing a really comprehensive and well-crafted album.[5]

—David Bowie, 1999

Rather than improvising lyrics and music as he had with prior releases, Bowie took time composing and developing the lyrics and melodies,[6][5] ensuring the musicians adhered to his thought-out structures before adding personal touches.[8] Many of the tracks had working titles early on. Some of the these included "People Are Turning to Gold" ("Ashes to Ashes"), "It Happens Everyday" ("Teenage Wildlife"), "Jamaica" ("Fashion"), "Cameras in Brooklyn" ("Up the Hill Backwards") and "I Am a Laser" ("Scream Like a Baby"), which was originally written and recorded in 1973 by a group of Bowie collaborators known as the Astronettes.[f].[6][13] Other tracks were recorded and left unfinished, including "Is There Life After Marriage?" and an instrumental cover of Cream's "I Feel Free"; the latter was fully covered for Black Tie White Noise (1993).[14] The lyrics for the title track, which dated back to a 1975 song called "Running Scared",[15] were written in response to a promotional campaign for Kellogg's Corn flakes cereal, which offered novelty toys of "Scary Monsters and Super Heroes".[5][10]

The sessions resumed in April 1980 at Good Earth Studios in London, Visconti's own studio at the time.[12] Final instrumental overdubs were provided by Fripp and the keyboardist Andy Clark, along with a guest appearance by the Who guitarist Pete Townshend on "Because You're Young".[5] Vocal tracks were recorded last,[5][16] including the Japanese narration provided by the actress Michi Hirota for "It's No Game (No. 1)".[17]

Music and lyrics

[edit]By the time of Scary Monsters the kind of music that I was doing was becoming very acceptable ... it was definitely the sound of the early eighties.[5]

—David Bowie, 1990

Commentators have classified Scary Monsters as art rock,[18] new wave, and post-punk.[19] Writing for AllMusic, Stephen Thomas Erlewine considers Scary Monsters to be a culmination of Bowie's 1970s works and the record's sound to be not "far removed from the post-punk of the early '80s".[20] Nicholas Pegg agrees, describing the record as "the triumphant culmination of Bowie's steely art-rock phase and a crucial doorway into early 1980s British pop".[5] In a career retrospective, Consequence of Sound described Scary Monsters as "a high watermark of art pop by which Bowie's future releases are still compared."[21] Carr and Murray describe the album's sound as being harsher – and his worldview more desperate – than anything he had released since Diamond Dogs (1974).[9] The biographer Christopher Sandford writes that lyrically, Scary Monsters reaffirms themes that Bowie had explored throughout his career up to that point, including madness, alienation and the "redeeming power of love"; in this case however, Bowie is able to bring the listener in instead of "freezing [them] out".[22]

Side one

[edit]The album opens with "It's No Game (No. 1)", which features sinister guitar loops and Bowie's screaming vocal performance,[23] which Chris O'Leary cites as reminiscent of John Lennon's performance on Plastic Ono Band (1970).[12] Partly taken from an older tune titled "Tired of My Life", it features lyrics read by the Japanese actress Michi Hirota, which were translated by Hisahi Miura. Hirota delivers her performance in what is described by Buckley as a "macho, samurai voice", which was done at Bowie's insistence as a way to "break down a particular type of sexist attitude about women".[17][23] James Perone writes that the track establishes the album's theme of "scary events".[24]

The lyrics of "Up the Hill Backwards" deal with the struggle of facing a crisis.[9] Bowie misquotes Thomas Anthony Harris's 1967 self-help book I'm OK – You're OK, a guide on how to save marriage relationships;[25] Carr and Murray see this as a reference to Bowie's divorce from Angie Bowie.[9] Musically, it features unusual time signatures and a Bo Diddley-inspired beat.[26][27] For the title track, the rhythm section took inspiration from Joy Division; Davis's drum performance has been compared to Stephen Morris's on "She's Lost Control" (1979).[28][12] Described by Perone as punk rock,[24] the music is heavily distorted, featuring Fripp's ferocious guitar-playing, Davis's pounding drums, and Bowie's treated Cockney accent. Lyrically, it follows a claustrophobic relationship between a woman (dating back to Bowie's Berlin days) and a man (the demons inside Bowie).[15][29]

"Ashes to Ashes" revisits the character of Major Tom from "Space Oddity" (1969). Over ten years later, Major Tom is described as a "junkie", which has been interpreted as parallel to Bowie's own struggles with drug addiction throughout the 1970s.[12][30] In 1990, Bowie acknowledged "Ashes to Ashes" as a confrontation of his past: "You have to accommodate your pasts within your persona. You have to understand why you went through them ... You cannot just ignore them to put them out of your mind or pretend they didn't happen, or just say, 'Oh, I was different then.'"[31] Musically, "Ashes to Ashes" is built around a guitar synthesiser theme by Hammer, augmented by Clark's synthesiser. Like "Space Oddity" before it, the song was built in stages, and features layers of instruments in its mix.[12] "Fashion" is reminiscent of Bowie's former single "Golden Years", with its mix of funk and reggae. It evolved out of a reggae "spoof" started by Clark on his synthesiser and features guitar "squeals" from Fripp. Apart from being a dance track, the song provokes elements of fascism, with lyrics such as "we are the goon squad" and "turn to the left, turn to the right".[12][32] The "beep beep" lines were taken from an earlier unreleased song titled "Rupert the Riley".[17]

Side two

[edit]

"Teenage Wildlife", the longest track on the album, is structurally similar to "'Heroes'" but does not feature a refrain; its verses only end with the title being sung over Fripp's guitar breaks. Its backing vocals are reminiscent of the Ronettes, while piano is provided by Roy Bittan.[12][33][34] The song's lyrics have been widely interpreted. One interpretation is they are an attack on Bowie imitators who emerged in the late 1970s, such as Gary Numan, who personally believed himself a target.[17] Carr and Murray state that the song is Bowie reflecting on his younger self,[9] while Pegg considers it a confrontation to critics who tried to prevent Bowie from evolving throughout the 1970s.[34] Bowie himself wrote in 2008 that the lyrics are about "taking a short view of life, not looking too far ahead and not predicting the oncoming hard knocks".[12] Although it descends from the early-mid 1970s "I Am a Laser", "Scream Like a Baby" features a contemporary new wave sound with lyrics of instability and political imprisonment, comparable with themes present on The Man Who Sold the World (1970).[9][12][35] Bowie recorded his vocal using varispeed, a technique that displays a "split personality" effect.[17]

"Kingdom Come", Bowie's first cover on a studio album since Station to Station,[36] is in the same key as Verlaine's original,[37] but is more grand in style.[12] Doggett describes the arrangement as "an unhappy cross between Motown sound and the sterility of American AOR".[37] Lyrically, the song features similar themes to other album tracks, including frustration, boredom and repetition.[37][24] On release, Bowie dedicated "Because You're Young" to his then nine-year-old son Duncan. Lyrically, the song is similar to other Scary Monsters tracks, featuring Bowie reflecting and advising a younger generation. Townshend's contributions are placed low in the mix.[12][38][39] The album ends with "It's No Game (No. 2)", which provides a stark contrast to "No. 1"; it features new lyrics and is more mellow and meditative throughout.[23] Doggett writes that whereas "No. 1" "climaxed with the signals of insanity", "No. 2" "just end[s], draining color from everything around it".[40] Similar to how the album begins, it ends with the sound of a tape rewinding and playing out, although this time, it slows to a halt.[12][23]

Artwork and packaging

[edit]

The cover artwork of Scary Monsters is a large-scale collage by the artist Edward Bell featuring Bowie in the Pierrot costume worn in the "Ashes to Ashes" music video, along with photographs taken by the photographer Brian Duffy. Duffy was reportedly upset by the final artwork, as he felt the cartoon demeaned his photographs.[5][41] The Pierrot costume, designed by Natasha Korniloff, was indebted to Bowie's time performing as a mime with the dancer Lindsay Kemp in the 1968 play Pierrot in Turquoise.[16]

The original LP's rear sleeve referred to four earlier albums, namely the immediately preceding Berlin Trilogy and 1973's Aladdin Sane, the latter also having been designed and photographed by Duffy. The cover images from Low, "Heroes" and Lodger—the last showing Bowie's torso superimposed on the figure from Aladdin Sane's inside gatefold picture—were portrayed in small whitewashed frames to the left of the tracklisting. The lettering used was a reworking of Gerald Scarfe's lettering for Pink Floyd's The Wall, which would be replicated on many album covers in the ensuing years.[5][41] These images were not reproduced on the Rykodisc reissue in 1992, but were restored for EMI/Virgin's 1999 remastered edition. The original framed album artwork was featured in the David Bowie Is touring museum exhibit.[42]

Release

[edit]The lead single, "Ashes to Ashes", was released in edited form by RCA Records on 1 August 1980, with the Lodger track "Move On" as the B-side.[12] It was issued in three different sleeves, the first 100,000 copies including one of four sets of stamps, all featuring Bowie in the Pierrot outfit he wore in the music video for the song.[30] The song was promoted with a music video, which at £250,000 (equivalent to £1,400,000 in 2023) was the most expensive music video ever made up to that point.[43] Directed by David Mallet, who directed all of Lodger's music videos,[44] the video depicts Bowie in a Pierot costume designed by his former collaborator Natasha Korniloff.[12] The single and video are both regarded by biographers as one of Bowie's finest,[43] with Pegg stating that it kickstarted the New Romantic movement.[30] The single debuted at No. 4 on the UK Singles Chart; after premiering the music video on the BBC television programme Top of the Pops, the single shot to No. 1, becoming Bowie's fastest-selling single and dethroning ABBA's "The Winner Takes It All". It was Bowie's second No. 1 single in the UK, after a reissue of "Space Oddity".[12][30][43] However, the US release, featuring "It's No Game (No. 1)" as the B-side, fared worse, peaking at No. 79 on the Cash Box Top 100 chart and No. 101 on the Billboard Bubbling Under the Hot 100 chart.[45]

Scary Monsters was released on 12 September 1980.[16] RCA promoted the album with the tagline "Often Copied, Never Equalled", seen as a direct reference to the new wave acts Bowie had inspired over the years.[41] The album was a major commercial success, peaking at No. 1 on the UK Albums Chart, his first since Diamond Dogs (1974), and remained on the chart for 32 weeks,[46] his longest since Aladdin Sane (1973).[5][47] The album restored Bowie's commercial standing in the US,[9] peaking at No. 12 on the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart and remained on the chart for 27 weeks.[48] Buckley writes that with Scary Monsters, Bowie achieved "the perfect balance" of creativity and mainstream success.[41]

The second single, "Fashion", was released in edited form on 24 October 1980, with "Scream Like a Baby" as the B-side.[49][50] The single was another commercial success, peaking at No. 5 in the UK and No. 70 in the US.[32] Like the first single, it was promoted by a music video again directed by Mallet. The video depicts Bowie and his backing musicians as "gum-chewing tough guys", interspersed with shots of dancers rehearsing and New Romantic followers. Like "Ashes to Ashes", the video was highly praised, with Record Mirror voting both as the best music videos of 1980.[32] The title track was released as the third single, again in edited form,[35] on 2 January 1981, backed by "Because You're Young".[50] The single continued Bowie's commercial success in the UK, peaking at No. 20.[49] The fourth and final single, "Up the Hill Backwards", was released in March 1981, with the non-album Japanese single "Crystal Japan" as the B-side.[50] It peaked at No. 32 in the UK, performing the worst out of all the singles.[49]

Critical reception

[edit]| Initial reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B+[51] |

| Record Mirror | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Smash Hits | 9/10[54] |

| Sounds | |

Scary Monsters received universal praise from music critics.[5] Record Mirror awarded it a rating of seven stars out of five;[52] the same publication voted Bowie the best male singer of 1980,[56] as did the Daily Mirror.[5] Smash Hits gave it a 9 out of 10 rating, describing it as "possibly his most consistently effective long player of all".[54] Melody Maker called it "an eerily impressive stride into the '80s",[57] while Billboard correctly predicted that it "should be the most accessible and commercially successful Bowie LP in years".[58] The Guardian's Robin Denselow agreed, describing Scary Monsters as being "full of accessible, highly original melodies that are increasingly inaccessible".[59]

Debra Rae Cohen of Rolling Stone found the record to be a "clarification" of Bowie's collaborations with Eno and similar in vein to Aladdin Sane, further finding Bowie "settling old scores" throughout Scary Monsters.[60] Fellow critic Dave Marsh considered it one of Bowie's best, saying "if this is the new art-rock, I'm for it."[53] The New York Daily News's Clint Roswell likewise hailed the record as Bowie's best in years, naming "Ashes to Ashes", "Fashion", "Because You're Young" and the title track as songs that recognise the artist as "the preminent figure in pop".[61] Adding further praise was James Johnson of the Evening Standard, who described the "remarkable" LP as one of the year's best and "proves that Bowie can still maintain his mastery of the rock mainstream whenever he feels like it".[62]

The Boston Globe's Jim Sullivan found side two weaker than the first, but concluded "Bowie continues to present a complex, invigorating challenge".[63] Tom Sowa was more mild in The Spokesman-Review. He hailed Scary Monsters as Bowie's finest in four years, highlighting Fripp's contributions and signalled out "Ashes to Ashes" and "Because You're Young", but panned "Teenage Wildlife" as "an overheated, confused and totally embarrassing four minutes of plastic".[64] Murray gave the album a more mixed assessment in NME, stating: "Scary Monsters is shorn of all hope, yet it represents a call to arms. It is an album which presupposes defeat, yet it is unashamedly and unequivocally confrontational." He further called it the "realist's" Bowie record.[65] In The New York Times, John Rockwell felt the album lacked appeal for all rock listeners due to it being "too misshapenly ugly. grindingly abrasive and proudly self-withholding. Nevertheless, he deemed it a "fine record of its particular type".[66]

On its end-of-the-year list, Record Mirror named Scary Monsters the second best album of the year, behind Sound Affects by the Jam,[56] while NME ranked it the ninth best album of the year.[67] On The Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop music critics' poll, it placed 19th.[68]

Subsequent events

[edit]Bowie decided not to support Scary Monsters on a concert tour. Instead, he continued his acting career by performing the lead role of Joseph "John" Merrick in the Broadway play The Elephant Man, which ran from July 1980 to January 1981, and guest starring as himself in the film Christiane F. (1981).[16][69][70] Following John Lennon's murder in December 1980, Bowie withdrew to his home in Switzerland and became a recluse.[69][70] Nevertheless, he continued working, recording the title song of the film Cat People (1982) with Giorgio Moroder and "Under Pressure" with the rock band Queen in July 1981.[71][72] The following month, Bowie performed the title role in a BBC adaptation of Bertolt Brecht's play Baal and recorded an accompanying soundtrack EP, both released in early 1982.[73] He also starred in the films The Hunger and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, both released in 1983.[74][75]

Bowie did not release another studio album until Let's Dance, released in April 1983.[76] Scary Monsters was also Bowie's final studio album for RCA Records, who had been his label since Hunky Dory (1971).[77] Bowie had grown increasingly dissatisfied with the label, who he felt was "milking" his back catalogue.[5] Although RCA was willing to re-sign, Bowie signed a new contract with EMI America Records,[78] and with Let's Dance, began an era of major commercial success.[79]

Influence and legacy

[edit]| Retrospective reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Spin | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 8/10[86] |

Retrospectively, Scary Monsters continues to receive acclaim. Jon Dolan of Spin wrote that although the 1980s were a less-than-stellar decade for the artist creatively, he began the decade strong with Scary Monsters, praising Bowie's vocal performance and describing "Ashes to Ashes" in particular as "gorgeous".[85] Erlewine praised the album for its culmination of Bowie's 1970s works: "While the music isn't far removed from the post-punk of the early '80s, it does sound fresh, hip, and contemporary, which is something Bowie lost over the course of the '80s."[20] Eduardo Rivadavia praised the record's "risk-taking creativity" in Ultimate Classic Rock, writing that the artist's decision to take time writing lyrics resulted in some of the best lyrics and vocal performances of his career. He ultimately called the album one of Bowie's "very best career efforts."[87] The author Peter Doggett describes Scary Monsters as one of Bowie's "most valuable statements", writing that it "annull[ed] audience expectations" and launched a "warning for those who might dare to follow in his footsteps."[88]

Reviewing the album's remaster for the 2017 box set A New Career in a New Town (1977–1982), Chris Gerard of PopMatters highlighted Bowie's vocal performance on the record as among his best, further complimenting the songs' arrangements and harmonies as "jaw-droppingly brilliant as anything you'll find in the realm of rock 'n' roll."[89] Analysing the album for its 40th anniversary in 2020, Stereogum's Ryan Leas described Scary Monsters as "the less-heralded classic of Bowie's career", complimenting the way Bowie was able to mesh the different eras of his career up to that point into a creative whole. Leas concluded: "[Scary Monsters] was the album that best-captured everything Bowie was about — and it will always be the conduit through which everything travelled, all of his old selves folded in and carried forward through the rest of his life.[90] In a 2013 readers' poll for Rolling Stone, Scary Monsters was voted Bowie's seventh greatest album. The magazine argued that it would be his final "satisfying from start to finish" album.[91]

Reflecting on the critical and commercial success of Scary Monsters, Visconti stated, "We kind of felt that we'd finally achieved our Sgt. Pepper, a goal we had in mind since The Man Who Sold the World."[5] Visconti further said: "It is one of my favourite Bowie albums ever."[92] Despite his glowing assessment of the album, Scary Monsters proved to be the final collaboration between Bowie and Visconti for over 20 years, after Bowie chose Nile Rodgers to produce Let's Dance.[5] Although Bowie would achieve worldwide mega-stardom and commercial success in the following years, in particular with Let's Dance, many commentators consider Scary Monsters to be "his last great album"[20][90] and the "benchmark" for each new release.[5] Well-regarded later efforts such as Outside (1995),[93] Earthling (1997),[94] Heathen (2002) and Reality (2003) were cited as "the best album since Scary Monsters."[95] Buckley suggested that "Bowie should pre-emptively sticker up his next album 'Best Since Scary Monsters' and have done with it".[96] The biographer Marc Spitz considers it more accurate to call the album Bowie's "last 'young' record", in that it was his final "perfectly confident statement" and the final time that Bowie's "search for the 'new' in our world of sound [felt] pure, as opposed to betraying itself".[27]

Bowie's biographers continue to praise Scary Monsters. Pegg writes that retrospectively, Scary Monsters sounds "as fresh and dynamic as ever", and ended "Bowie's golden run of cutting-edge albums."[5] O'Leary described it in 2019 as Bowie's most "modern"-sounding album.[12] Spitz finds the record to have an energy that his later "good" albums don't (naming Outside and Heathen).[27] Doggett considers it as one of Bowie's "most valuable statements", exceeding his listeners' expectations while at the same time sending a warning out to anyone who dared to follow in his footsteps.[88] Sandford states that with Scary Monsters, Bowie "found his voice again" after years of experimentation.[22] Perone praises the album as "a near-perfect balance of [Bowie's] pop and experimental sides" and that it remains one of the artist's "most important and consistent albums".[24] In 2011, Paul Trynka wrote: "Scary Monsters still sparkles today. Its intense, churning grooves sound remarkably contemporary ... but despite the complexity of its arrangements there are many moments of unaffected simplicity."[97] He considers the album's "dense, tough, rock-meets-funk backup" as influential on later bands such as Blur and the Strokes.[98] The American electronic music producer Skrillex named his 2010 EP Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites after Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps).[99]

Rankings

[edit]Scary Monsters has appeared on several lists of the greatest albums of all time by multiple publications. In 2000, Q ranked Scary Monsters at number 30 on its list of the "100 Greatest British Albums Ever".[100] In 2002, Pitchfork placed it at number 93 on its list of the top 100 albums of the 1980s.[101] In 2012, Slant Magazine listed the album at number 27 on its list of the 100 best albums of the 1980s, saying "Bowie bridles the experimentation of his Berlin trilogy and channels those synth flourishes and off-kilter guitar licks into one of the decade's quirkiest pop albums."[102] In 2013, NME ranked the album at number 381 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[103] In 2018, Pitchfork placed it at number 53 on its revised list of the 200 best albums of the 1980s.[104] In 2020, Rolling Stone placed it at number 443 on its revision of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[105]

Reissues

[edit]The album has been rereleased five times to date on compact disc. It was first released on CD by RCA in the mid-1980s. A second CD release, in 1992 by Rykodisc and EMI, contained four bonus tracks.[106] A 1999 CD release by EMI/Virgin, with no bonus tracks, featured 24-bit digitally-remastered sound.[107] The album was re-released in 2003 by EMI as a Super Audio CD, again with no bonus tracks.[108] In 2017, the album was remastered for the A New Career in a New Town (1977–1982) box set released by Parlophone.[109] It was released in CD, vinyl, and digital formats, both as part of this compilation and then separately the following year.[89][110]

Track listing

[edit]All songs written by David Bowie, except where noted.

| No. | Title | Lyrics | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "It's No Game (No. 1)" | Bowie, trans. Hisahi Miura | 4:20 |

| 2. | "Up the Hill Backwards" | 3:15 | |

| 3. | "Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)" | 5:12 | |

| 4. | "Ashes to Ashes" | 4:25 | |

| 5. | "Fashion" | 4:49 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Teenage Wildlife" | 6:56 | |

| 2. | "Scream Like a Baby" | 3:35 | |

| 3. | "Kingdom Come" | Tom Verlaine | 3:45 |

| 4. | "Because You're Young" | 4:54 | |

| 5. | "It's No Game (No. 2)" | 4:22 |

Personnel

[edit]Albums credits per the liner notes and biographer Nicholas Pegg.[5][111]

- David Bowie – vocals, synthesisers, Mellotron, electric piano, piano, synth-bass, sound effects, backing vocals, saxophone

- Dennis Davis – drums

- George Murray – bass

- Carlos Alomar – lead and rhythm guitars

- Chuck Hammer – guitar synthesiser (on "Ashes to Ashes" and "Teenage Wildlife")

- Robert Fripp – guitar (on "Fashion", "It's No Game", "Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)", "Kingdom Come", "Up the Hill Backwards", and "Teenage Wildlife")

- Roy Bittan – piano (on "Ashes to Ashes", "Teenage Wildlife", and "Up the Hill Backwards")

- Andy Clark – synthesiser (on "Fashion", "Scream Like a Baby", "Ashes to Ashes" and "Because You're Young")

- Pete Townshend – guitar (on "Because You're Young")

- Tony Visconti – acoustic guitar (on "Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)" and "Up the Hill Backwards"), backing vocals

- Lynn Maitland – backing vocals

- Chris Porter – backing vocals

- Michi Hirota – voice (on "It's No Game (No. 1)")

Production

- David Bowie, Tony Visconti – production and engineering

- Larry Alexander, Jeff Hendrickson – engineering assistance

- Peter Mew, Nigel Reeve – mastering

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[135] | Platinum | 50,000^ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[136] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| France (SNEP)[137] | Gold | 100,000* |

| Germany | — | 70,000[138] |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[139] | Platinum | 300,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[140] | Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

| Summaries | ||

| Worldwide | — | 4,300,000[141] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

[edit]- ^ The album title is written on the front and back covers of the LP sleeve as Scary Monsters . . . . . and Super Creeps, and is identified simply as Scary Monsters on the LP spine and disc label.

- ^ Belew nevertheless received an advance to play on the record.[8]

- ^ Springsteen and the E Street Band were recording The River in the adjacent studio at the same time as Scary Monsters.[10]

- ^ "Crystal Japan" was released as a single in Japan, making its first appearance in a 1980 Japanese television commercial for the Shōchū drink Crystal Jun Rock.[11][12]

- ^ Although Verlaine arrived at the studio and tried out different guitar sounds, although Visconti said none of his playing was used, "if we even recorded him."[12]

- ^ The Astronettes were the singer Ava Cherry and Bowie's childhood friend Geoff MacCormack.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ Mastropolo, Frank (11 January 2016). "The History of David Bowie's Berlin Trilogy: 'Low,' 'Heroes,' and 'Lodger'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Buckley 1999, p. 302.

- ^ Spitz 2009, p. 290.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 308–314.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Pegg 2016, pp. 397–401.

- ^ a b c Buckley 2005, pp. 314–316.

- ^ Gittins, Ian (2007). "Art Decade". Mojo (60 Years of Bowie ed.). pp. 70–73.

- ^ a b Clerc 2021, p. 304.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 108–114.

- ^ a b Clerc 2021, pp. 304–306.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s O'Leary 2019, chap. 4.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 234–235, 398.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 120, 133.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, p. 234.

- ^ a b c d Clerc 2021, p. 306.

- ^ a b c d e Buckley 2005, pp. 322–323.

- ^ DeMain, Bill (2 September 2020). "How David Bowie returned to orbit and made Scary Monsters". Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Blackard, Cat; Graves, Wren; Manning, Erin (6 January 2016). "A Beginner's Guide to David Bowie". Consequence. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Scary Monsters – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Goble, Blake; Blackard, Cap; Levy, Pat; Phillips, Lior; Sackllah, David (8 January 2018). "Ranking: Every David Bowie Album from Worst to Best". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ a b Sandford 1997, p. 203.

- ^ a b c d Pegg 2016, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b c d Perone 2007, pp. 79–85.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 369–370.

- ^ a b c Spitz 2009, p. 311.

- ^ Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 112–115.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 370–371.

- ^ a b c d Pegg 2016, pp. 27–30.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 372–374.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 89–91.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 377–380.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 277–278.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 146–147.

- ^ a b c Doggett 2012, pp. 381–382.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 35.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 382–383.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 368–369.

- ^ a b c d Buckley 2005, pp. 321–322.

- ^ Sheridan, Linda (5 March 2018). "Sound & Vision: 'David Bowie is' Opens at the Brooklyn Museum". City Guide. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Buckley 2005, pp. 316–317.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 304–307.

- ^ Whitburn 2015, p. 57.

- ^ Sandford 1997, p. 204.

- ^ "Scary Monsters and Super Creeps – Official Chart History". UK Albums Chart. Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Scary Monsters Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ a b c O'Leary 2019, Partial Discography.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 781.

- ^ Christgau 1990.

- ^ a b Ludgate, Simon (20 September 1980). "Bowie Takes a Bow" (PDF). Record Mirror. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ a b Marsh, Dave (28 November 1980). "David Bowie: Scary Monsters (RCA)". Rolling Stone. The Charlotte Observer. p. 56. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Hepworth, David (2–15 October 1980). "David Bowie: Scary Monsters". Smash Hits. Vol. 2, no. 20. p. 29.

- ^ Veene, Valac Van Der (16 August 1980). "The fright of your life". Sounds. p. 43.

- ^ a b "Poll 1980 Results" (PDF). Record Mirror. 10 January 1981. pp. 16–17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Humphrey, Patrick (2007). "You've Been Around". Mojo (60 Years of Bowie ed.). p. 79.

- ^ "Top Album Picks" (PDF). Billboard. 20 September 1980. p. 70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Denselow, Robin (8 October 2014). "From the archive, 8 October 1980: Robin Denselow reviews new work from Springsteen and Bowie". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Debra Rae (25 December 1980). "Scary Monsters". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Roswell, Clint (14 December 1980). "Rock discs from Santa and punk platters too". Daily News. p. 572. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Johnson, James (23 September 1980). "Pick An Album: David Bowie – Scary Monsters". Evening Standard. p. 29. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sullivan, Jim (2 October 1980). "David Bowie: Scary Monsters (RCA)". The Boston Globe. p. 70. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sowa, Tom (31 October 1980). "David Bowie: Scary Monsters (RCA AQLI 3647)". The Spokesman-Review. p. 53. Archived from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Murray, Charles Shaar (20 September 1980). "David Bowie: Scary Monsters (RCA)". NME. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2021 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Rockwell, John (21 September 1980). "David Bowie's 'Scary Monsters'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ "NME's best albums and tracks of 1980". NME. 10 October 2016. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "The 1980 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. 9 February 1981. Archived from the original on 8 March 2005. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 662–664.

- ^ a b Buckley 2005, pp. 324–325.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 57, 291–292.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 389–390.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 665–667.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 667–670.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 390.

- ^ Clerc 2021, pp. 324–327.

- ^ Sandford 1997, p. 81.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 334–335.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 403.

- ^ Wolk, Douglas (July 2006). "David Bowie: Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)". Blender. No. 49.

- ^ Kot, Greg (10 June 1990). "Bowie's Many Faces Are Profiled On Compact Disc". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Larkin 2011.

- ^ "David Bowie: Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)". Q. No. 158. November 1999. pp. 140–141.

- ^ Sheffield 2004, p. 97.

- ^ a b Dolan, Jon (July 2006). "How to Buy: David Bowie". Spin. Vol. 22, no. 7. p. 84. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Sheffield 1995, p. 55.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo (12 September 2015). "Revisiting David Bowie's 'Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ a b Doggett 2012, p. 384.

- ^ a b Gerard, Chris (12 October 2017). "Filtered Through the Prism of David Bowie's Quixotic Mind: 'A New Career in a New Town'". PopMatters. p. 2. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ a b Leas, Ryan (11 September 2020). "David Bowie's 'Scary Monsters' at 40: The Hidden Classic of His Career". Stereogum. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ "Readers' Poll: The Best David Bowie Albums". Rolling Stone. 16 January 2013. Archived from the original on 29 May 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ Trynka 2011, p. 355.

- ^ Sullivan, Jim (12 April 1993). "New wife, new album keep David Bowie in fine spirits". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Kemp, Mark (20 February 1997). "David Bowie: Earthling". Rolling Stone. No. 754. pp. 65–66. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Easlea, Daryl (20 November 2002). "David Bowie Reality Review". BBC Music. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 500.

- ^ Trynka 2011, p. 353.

- ^ Trynka 2011, p. 489.

- ^ Bain, Katie (21 November 2019). "Songs that defined the decade: Skrillex's 'Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites'". Billboard. Archived from the original on 18 August 2023. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest British Albums Ever! – David Bowie: Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)". Q. No. 165. June 2000. p. 74.

- ^ "The Top 100 Albums of the 1980s". Pitchfork. 21 November 2002. p. 1. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of the 1980s". Slant Magazine. 5 March 2012. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time: 400–301". NME. 23 October 2013. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "The 200 Best Albums of the 1980s". Pitchfork. 10 September 2018. p. 8. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (CD liner notes). David Bowie. US: Rykodisc. 1992. RCD 20147.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (CD liner notes). David Bowie. Europe/US: EMI/Virgin Records. 1999. 7243 521895 0 2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (SACD liner notes). David Bowie. UK & Europe: EMI. 2003. 07243 543318 2 4.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "A New Career In A New Town (1977–1982)". David Bowie Official Website. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Grow, Kory (28 September 2017). "Review: David Bowie's Heroically Experimental Berlin Era Explored in 11-CD Box Set". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (liner notes). David Bowie. UK: RCA Records. 1980. BOW LP 2.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b Kent, David (1993). Kent Music Report: Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 978-0-646-11917-5.

- ^ "David Bowie – Scary Monsters" (ASP). austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on 12 December 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "Top Albums/CDs". RPM. Vol. 34, no. 6. 20 December 1980. Archived from the original (PHP) on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "Hits of the World" (PDF). Billboard. 14 March 1981. p. 67. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ "David Bowie – Scary Monsters" (ASP). dutchcharts.nl. MegaCharts. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2021). "David Bowie". Sisältää hitin - 2. laitos Levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla 1.1.1960–30.6.2021 (PDF) (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava. pp. 36–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "InfoDisc : Tous les Albums classés par Artiste > Choisir Un Artiste Dans la Liste". infodisc.fr. Archived from the original (PHP) on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2014. Note: user must select 'David BOWIE' from drop-down.

- ^ Oricon Album Chart Book: Complete Edition 1970–2005. Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. 2006. ISBN 978-4-87131-077-2.

- ^ "David Bowie – Scary Monsters" (ASP). charts.nz. Recording Industry Association of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "David Bowie – Scary Monsters" (ASP). norwegiancharts.com. VG-lista. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 978-84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "David Bowie – Scary Monsters" (ASP). swedishcharts.com. Sverigetopplistan. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "David Bowie | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "Scary Monsters Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "Album Search: David Bowie – Scary Monsters" (in German). Media Control. Archived from the original (ASP) on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – David Bowie – Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)". Hung Medien. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – David Bowie – Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps)". Hung Medien. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2018. 9. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "RPM Top 100 Albums of 1980". RPM. 20 December 1980. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "Dutch charts jaaroverzichten 1980" (ASP) (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 1980 — The Official New Zealand Music Chart". Recorded Music New Zealand. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Chart File". Record Mirror. 4 April 1981. p. 38.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums of 1981". RPM. 26 December 1981. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Kent Music Report No 341 – 5 January 1981 > Platinum and Gold Albums 1980". Kent Music Report. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021 – via Imgur.com.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – David Bowie – Scary Monsters". Music Canada. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "French album certifications – Bowie D. – Scary Monsters" (in French). InfoDisc. Select BOWIE D. and click OK.

- ^ "Bowie LP Is German Smash". Billboard. 27 September 1980. p. 58. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ "British album certifications – David Bowie – Scary Monsters". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "American album certifications – David Bowie – Scary Monsters". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ Breteau, Pierre (11 January 2016). "David Bowie en chiffres : un artiste culte, mais pas si vendeur". Le Monde. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Buckley, David (1999). Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-1-85227-784-0.

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-1002-5.

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record. London: Eel Pie Publishing. ISBN 978-0-380-77966-6.

- Christgau, Robert (1990). "David Bowie: Scary Monsters". Christgau's Record Guide: The '80s. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-679-73015-6. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- Clerc, Benoît (2021). David Bowie All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. New York City: Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-0-7624-7471-4.

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York City: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). "Bowie, David". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- O'Leary, Chris (2019). Ashes to Ashes: The Songs of David Bowie 1976–2016. London: Repeater. ISBN 978-1-912248-30-8.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (revised and updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Perone, James E. (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27599-245-3. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- Sandford, Christopher (1997) [1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. London: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80854-8.

- Sheffield, Rob (1995). "David Bowie". In Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig (eds.). Spin Alternative Record Guide. New York City: Vintage Books. pp. 55–57. ISBN 978-0-679-75574-6.

- Sheffield, Rob (2004). "David Bowie". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-0169-8.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-03225-4.

- Whitburn, Joel (2015). The Comparison Book. Menonomee Falls, Wisconsin: Record Research Inc. ISBN 978-0-89820-213-7.

External links

[edit]- Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) at Discogs (list of releases)