Oakland Athletics

| Oakland Athletics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Information | |||||

| League | American League (1968–2024) West Division (1969–2024) | ||||

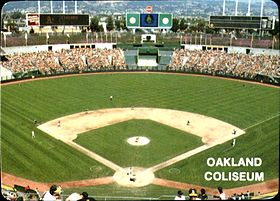

| Ballpark | Oakland Coliseum (1968–2024) | ||||

| Established | 1901 (franchise, Philadelphia) 1968 (Oakland) | ||||

| Relocated | 2024 (to West Sacramento, California; became the Athletics) | ||||

| Nickname(s) | The A's

| ||||

| American League pennant | 15 (6 in Oakland) | ||||

| West Division titles | 17 | ||||

| World Series championships | 9 (4 in Oakland) | ||||

| Wild Card championships | 4 | ||||

| Colors | Green, gold, white[a][2][3] | ||||

| Mascot | Stomper Trunk Harry Elephante Charlie-O | ||||

| Retired numbers | |||||

| Ownership | List of owners

| ||||

| Manager | List of managers

| ||||

| General Manager | List of general managers

| ||||

| President | List of presidents

| ||||

| Uniforms | |||||

| |||||

The Oakland Athletics (often referred to as the Oakland A's) were an American professional baseball team based in Oakland, California. The Oakland Athletics competed in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) West Division from 1968 until 2024. The team played its home games at the Oakland Coliseum throughout their entire time in Oakland. The franchise's nine World Series championships, fifteen pennants, and seventeen division titles are the second-most in the AL after the New York Yankees.

Despite the team's success in Oakland, issues with the Oakland Coliseum throughout the decades led to the team trying to replace the aging venue multiple times, but after they were not able to secure locations in East Bay and San Jose, the team left Oakland after the 2024 season, temporarily moving to West Sacramento before a permanent move to Las Vegas. The move from Oakland was the franchise's third relocation after Philadelphia and Kansas City. The move also marked the end of professional major league sports in Oakland, as the California Golden Seals of the NHL, who had played at the next door Oakland Arena, relocated to Cleveland in 1976, the Golden State Warriors of the NBA, who also played at Oakland Arena, moved across the bay to San Francisco in 2019 and their former co-tenant Oakland Raiders of the NFL relocated to Las Vegas in 2020.

The Oakland Athletics had an overall win–loss record of 4,614–4,387–1 (.513) during their 56 years in Oakland. Seventeen former Oakland Athletics players were elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame with Dennis Eckersley, Rollie Fingers, Rickey Henderson, and Dick Williams depicted with an Oakland Athletics cap.

History

[edit]Relocation from Kansas City

[edit]Almost as soon as the ink dried on his purchase of the Athletics in 1960, Finley began shopping the Athletics to other cities despite his promises that the A's would remain in Kansas City. Soon after the lease-burning stunt, it was discovered that what actually burned was a blank boilerplate commercial lease available at any stationery store. The actual lease was still in force—including the escape clause. Finley later admitted that the whole thing was a publicity stunt, and he had no intention of amending the lease.[citation needed]

In 1961 and 1962, Finley talked to people in Dallas–Fort Worth and a four-man group appeared before American League owners,[4] but no formal motion was put forward to move the team to Texas. In January 1964, he signed an agreement on to move the A's to Louisville,[5] promising to change the team's name to the "Kentucky Athletics".[6] (Other names suggested for the team were the "Louisville Sluggers" and "Kentucky Colonels", which would have allowed the team to keep the letters "KC" on their uniforms.) The owners turned it down by a 9–1 margin on January 16, with Finley being the only one voting in favor.[7] Six weeks later, by the same 9–1 margin, the AL owners denied Finley's request to move the team to Oakland.

These requests came as no surprise, as impending moves to these cities, as well as to Atlanta, Milwaukee, New Orleans, San Diego, and Seattle—all of which Finley had considered as new homes for the Athletics—had long been afloat. He also threatened to move the A's to a "cow pasture" in Peculiar, Missouri, complete with temporary grandstands.[8] Not surprisingly, attendance tailed off. The city rejected Finley's offer of a two-year lease agreement;[9] finally, American League President Joe Cronin persuaded Finley to sign a four-year lease with Municipal Stadium in February 1964.[10]

During the World Series on October 11, 1967, Finley announced his choice of Oakland over Seattle as the team's new home.[11][12] A week later on October 18 in Chicago, AL owners at last gave him permission to move the Athletics to Oakland for the 1968 season.[13][14] According to some reports, Cronin promised Finley that he could move the team after the 1967 season as an incentive to sign the new lease with Municipal Stadium. The move came in spite of approval by voters in Jackson County, Missouri, of a bond issue for a brand new baseball stadium (the eventual Royals Stadium, now Kauffman Stadium) to be completed in 1973.

A new home and the emergence of a powerhouse (1968–1970)

[edit]The Athletics' Oakland tenure opened with a 3–1 loss to the Baltimore Orioles on April 10, 1968, and their first game in Oakland was on April 17, a 4–1 loss to the Orioles. They played their home games at the recently opened Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum, the home of the AFL's Oakland Raiders, with whom they shared the stadium. The Athletics drew national attention when, on May 8, 1968, Jim "Catfish" Hunter pitched a perfect game (the American League's first during the regular season since 1922) against the Minnesota Twins. The Athletics, under the leadership of manager Bob Kennedy, ended the 1968 campaign with an 82–80 record, their first winning record since 1952 (in Philadelphia). The team's output also represented a 20-win increase over the prior year's 62–99 finish. Bob Kennedy was fired at the end of the season.[15]

Expansion brought optimism to Athletics fans after AL owners (unlike their counterparts in the National League) decided to realign their league strictly based on geography. Despite finishing in sixth place and only two games above .500 in 1968, Oakland actually had the best record of the four established teams to join the AL West, which also contained the two expansion teams. The Athletics began the 1969 season under the leadership of Hank Bauer. On July 20, 1969, future ace Vida Blue made his major league debut with a start against the California Angels. The Athletics' on-field performance continued to improve; led by Reggie Jackson's 47 home runs, the A's finished the season with a record of 88–74. However, this was only good enough for second place behind the Minnesota Twins, and was not good enough for Finley, who had been expecting his team to win the division title. Hank Bauer was fired (and replaced with John McNamara) near the end of the season. The team's record stood at 80–69 at the time of his firing. McNamara himself would be fired following an 89–73 finish in 1970. He was replaced by former Boston Red Sox manager Dick Williams.[16]

Swingin' A's (1971–1975)

[edit]The Athletics, following two consecutive second-place finishes, finally claimed the division crown in 1971. The A's would win 101 games (their first 100-win season since finishing 107–45 in 1931). However, they lost to the Baltimore Orioles in the American League Championship Series. In 1972, the A's won their first league pennant since 1931 and faced the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series.[17]

That year, the A's began wearing solid green or solid gold jerseys, with contrasting white pants, at a time when most other teams wore all-white uniforms at home and all-grey ones on the road. Similar to more colorful amateur softball uniforms, they were considered a radical departure for their time. Furthermore, in conjunction with a Moustache Day promotion, Finley offered $300 to any player who grew a moustache by Father's Day, at a time when every other team forbade facial hair. When Father's Day arrived, every member of the team collected a bonus. The 1972 World Series against the Cincinnati Reds was termed "The Hairs vs. the Big Squares", as the Reds wore more traditional uniforms and required their players to be clean-shaven and short-haired. A contemporaneous book about the team was called Mustache Gang. The A's seven-game victory over the heavily favored Reds gave the team its first World Series Championship since 1930.[18]

They defended their title in 1973 and 1974. Unlike Mack's champions, who thoroughly dominated their opposition, the A's teams of the 1970s played well enough to win their division (which was usually known as the "American League Least" during this time). They then defeated teams that had won more games during the regular season with good pitching, good defense, and clutch hitting. Finley called this team the "Swingin' A's". Players such as Reggie Jackson, Sal Bando, Joe Rudi, Bert Campaneris, Catfish Hunter, Rollie Fingers, and Vida Blue formed the nucleus of these teams.[citation needed]

The players often said in later years that they played so well as a team because almost to a man, they hated Finley with a passion. For instance, Finley threatened to pack Jackson off to the minors in 1969 after Jackson hit 47 homers; Commissioner Bowie Kuhn had to intervene in their contract dispute. Kuhn intervened again after Blue won the AL Cy Young Award in 1971 and Finley threatened to send him to the minors. Finley's tendency for micromanaging his team actually dated to the team's stay in Kansas City. Among the more notable incidents during this time was a near-mutiny in 1967; Finley responded by releasing the A's best hitter, Ken Harrelson, who promptly signed with the Red Sox and helped lead them to the pennant.[citation needed]

The Athletics' victory over the New York Mets in the 1973 Series was marred by Finley's antics. Finley forced Mike Andrews to sign a false affidavit saying he was injured after the reserve second baseman committed two consecutive errors in the 12th inning of the A's Game Two loss to the Mets. When Williams, Andrews' teammates, and virtually the entire viewing public rallied to Andrews' defense, Kuhn forced Finley to back down. However, there was nothing that said the A's had to play Andrews. Andrews entered Game 4 in the eighth inning as a pinch-hitter to a standing ovation from sympathetic Mets fans. He promptly grounded out, and Finley ordered him benched for the remainder of the Series. Andrews never played another major league game. As it was, the incident allowed the Mets, a team that went but 82–79 during the regular season, to stretch the Series to the full seven games against a far superior team. Williams was so disgusted by the affair that he resigned after the Series. Finley retaliated by vetoing Williams' attempt to become manager of the Yankees. Finley claimed that since Williams still owed Oakland the last year of his contract, he could not manage anywhere else. Finley relented later in 1974 and allowed Williams to take over as manager of the California Angels.[citation needed]

After the Athletics' victory over the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 1974 Series (under Alvin Dark), pitcher Catfish Hunter filed a grievance, claiming that the team had violated its contract with Hunter by failing to make timely payment on an insurance policy during the 1974 season as called for. On December 13, 1974, arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled in Hunter's favor. As a result, Hunter became a free agent, and signed a contract with the Yankees for the 1975 season. Despite the loss of Hunter, the A's repeated as AL West champions in 1975, but lost the ALCS to Boston in a 3-game sweep.

Free agency, the dismantling of the A's, and the end of the Finley years

[edit]1975

[edit]In 1975, fed up with poor attendance in Oakland during the team's championship years, Finley thought of moving yet again. When Seattle filed a lawsuit against Major League Baseball over the move of the Seattle Pilots to Milwaukee, Finley and others came up with an elaborate shuffle which would move the ailing Chicago White Sox to Seattle. Finley then would move the A's to Chicago, closer to his home in LaPorte, Indiana; and take the White Sox' place at Comiskey Park. The scheme fell through when White Sox owner John Allyn sold the team to another colorful owner, Bill Veeck, who was not interested in leaving Chicago.

1976

[edit]As the 1976 season got underway, the basic rules of player contracts were changing. Seitz had ruled that baseball's reserve clause only bound players for one season after their contract expired. Thus, all players not signed to multi-year contracts would be eligible for free agency at the end of the 1976 season. The balance of power had shifted from the owners to the players for the first time since the days of the Federal League. Like Mack had done twice before, Finley reacted by trading star players and attempting to sell others. On June 15, 1976, Finley sold left fielder Rudi and relief pitcher Fingers to Boston for $1 million each, and pitcher Blue to the New York Yankees for $1.5 million. Three days later, Kuhn voided the transactions in the "best interests of baseball". Amid the turmoil, the A's still finished second in the AL West, 2.5 games behind the Royals.

1977

[edit]After the 1976 season, most of the Athletics' veteran players did become eligible for free agency, and predictably almost all left. More than 40 years and 3,000 miles (4,800 km) after Connie Mack's last dynasty, one of baseball's most storied franchises suffered yet another dismemberment of a dynasty team. As happened with the end of the A's first dynasty in the early 1900s, the collapse was swift, sudden and total. The next three years were as bad as the worst days in Philadelphia or Kansas City, with the A's finishing last twice and next-to-last once. In 1977, for instance—only three years after winning the World Series and two years after playing for the pennant—the A's finished with the worst record in the American League, and the second-worst record in baseball. They even trailed the expansion Seattle Mariners (though by only 1⁄2 game, as one game with the Minnesota Twins was canceled by weather and never made up).

At the end of the 1977 season, Finley attempted to trade Blue to the Reds for a player of lesser stature and cash, but Kuhn vetoed the deal, claiming that it was tantamount to a fire sale similar to the sales he voided a year earlier. He also claimed that adding Blue to the Reds' already formidable pitching staff would make a mockery of the National League West race. Later, Finley sent Doug Bair to the Reds in a deal that Kuhn deemed a true trade. At the same time, Blue was traded across the bay to the San Francisco Giants in a multi-player trade that likewise received the Commissioner's blessing.

1978–1980

[edit]Despite Finley's reputation as a master promoter, the A's had never drawn well since moving to Oakland, even during the World Series years. In the three years after the veterans from the championship years left, attendance dropped so low that the Coliseum became known as the "Oakland Mausoleum". At one point during the late 1970s, crowds could be counted in the hundreds. The low point came in 1979, when an April 17 game against the Mariners drew an announced crowd of 653. However, A's officials claimed the actual attendance was 550, while first baseman Dave Revering thought the crowd was closer to 200. What is beyond dispute is that it was the smallest "crowd" in the West Coast portion of A's history.[19] The Coliseum's upkeep also went downhill. The franchise's rapid deterioration so soon after being the most powerful team in the game led some fans to nickname them "the Triple-A's".

For most of Finley's ownership, the A's rarely had radio or television contracts, rendering them all but invisible in the Bay Area even during the World Series era. For the first month of the 1978 season, the A's broadcast their games on KALX, a 10-watt college radio station run by the University of California, Berkeley.[19] KALX was practically unlistenable more than 10 miles (16 km) from Oakland. At that time, the A's had a radio network stretching all the way to Hawaii, leading one fan to joke, "Honolulu? How about here?"[20] In 1979, the A's did not sign a radio contract until the night before opening day. The A's near-invisibility prompted Oakland and Alameda County to sue Finley and the A's for breach of contract in 1979.[19]

Finley nearly sold the team to buyers who would have moved them to Mile High Stadium in Denver for the 1978 season and the Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans for 1979. Though the American League owners appeared to favor the Denver deal, it fell through when the city of Oakland and Alameda County refused to release the A's from their lease. At the time, the Oakland Raiders were threatening to move to Los Angeles, and city and county officials were not willing to lose Oakland's status as a big-league city in its own right. Not surprisingly, only 306,763 paying customers showed up to watch the A's in 1979, the team's worst attendance since leaving Philadelphia.

After three dismal seasons on the field and at the gate, the commissioner's office seriously considered selling the team out from under Finley and moving it to New Orleans. Rather than acquiesce, Finley hired Berkeley native Billy Martin to manage the young team, led by new young stars Rickey Henderson, Mike Norris, Tony Armas, and Dwayne Murphy. Martin made believers of his young charges, "Billyball" was used to market the team, and the Athletics finished second in 1980.[21]

However, during that same season Finley's wife sought a divorce, and would not accept a stake in the A's in a property settlement. With most of his money tied up in the A's or his insurance empire, Finley had to sell the team. He agreed in principle to sell to businessman Marvin Davis, who would have moved the Athletics to Denver. However, just before Finley and Davis were due to sign a definitive agreement, the Raiders announced their move to Los Angeles. Oakland and Alameda County officials let it be known that they would not allow any prospective owner to break the Coliseum lease, forcing Davis to call off the deal. Forced to turn to local buyers, Finley sold the A's to San Francisco clothing manufacturer Walter A. Haas, Jr., president of Levi Strauss & Co. prior to the 1981 season. It would not be the last time that the Raiders directly affected the A's future; Denver would eventually get an MLB team in 1993 when the Colorado Rockies began play.

Local ownership for the Athletics: the Haas era (1981–1995)

[edit]

Despite winning three World Series and two other AL West Division titles, the A's on-field success did not translate into success at the box office during the Finley era in Oakland. Average home attendance from 1968 to 1980 was 777,000 per season, with 1,075,518 in 1975 being the highest attendance for a Finley-owned team. In marked contrast, during the first year of Haas' ownership, the Athletics drew 1,304,052—in a season shortened by a player strike. Were it not for the strike, the A's were on a pace to draw over 2.2 million in 1981. This lent credence to the theory that Bay Area residents stayed away from the Coliseum because they did not want to give their money to Finley.[19]

Haas set about changing the team's image. He ditched Charlie O. as the team mascot and restored the traditional team name of "Athletics" as soon as he closed on the purchase, with the ownership group formally known as "The Oakland Athletics Baseball Company". He also installed pictures of Connie Mack and other greats from the Philadelphia days in the team office; Finley had scarcely acknowledged the team's past. While the team colors remained green, gold, and white, the bright Kelly green was replaced with a more subdued forest green. After a 23-year hiatus, the elephant was restored as the club mascot in 1988. The script "Athletics", which had adorned home and road jerseys from 1954 to 1960, was returned to home jerseys in 1987.

The Haases gave Martin complete control of the baseball operation with the title of "player development director", effectively making him his own general manager. The A's lost in the American League Championship Series after winning the "first half" AL West Division title of the strike-interrupted 1981 season. The club finished with the second-best overall record in baseball, and the best record in the American League. Had the season not been split in half, the 1981 A's would have gone wire-to-wire. However, an injury-riddled team significantly regressed in 1982, falling to 68–94. Although Martin was not blamed for the debacle, growing concern about his off-field behavior resulted in his firing after the season.

During the 15 years of Haas' ownership, the Athletics became one of baseball's most successful teams at the gate, drawing 2,900,217 in 1990, still the club record for single season attendance, as well as on the field. Average annual home attendance during those years (excluding the strike years of 1981 and 1994) was over 1.9 million.

Under the Haas ownership, the minor league system was rebuilt, which bore fruit later that decade as José Canseco (1986), Mark McGwire (1987), and Walt Weiss (1988) were chosen as AL Rookies of the Year. During the 1986 season, Tony La Russa was hired as the Athletics' manager, a post he held until the end of 1995. In 1987, La Russa's first full year as manager, the team finished at 81–81, its best record in seven seasons. Beginning in 1988, the Athletics won the AL pennant three years in a row. Reminiscent of their Philadelphia predecessors, this A's team finished with the best record of any team in the major leagues during all 3 years, winning 104 (1988), 99 (1989), and 103 (1990) games, featuring such stars as McGwire, Canseco, Weiss, Rickey Henderson, Carney Lansford, Dave Stewart, and Dennis Eckersley.

During this time, Rickey Henderson shattered Lou Brock's modern major league record by stealing 130 bases in a single season (1982), a total which has not been approached since. On May 1, 1991, Henderson broke one of baseball's most famous records when he stole the 939th base of his career, one more than Brock.

Regular season dominance led to some success in the post-season. The Athletics' lone World Series championship of the era was a four-game sweep of the cross-bay rival San Francisco Giants in the 1989 World Series. Unfortunately for the A's, their sweep of the Giants was overshadowed by the Loma Prieta earthquake that occurred at the start of Game 3 before a national television audience. This forced the remaining games to be delayed for ten days. When play resumed, the atmosphere was dominated more by a sense of relief than celebration by baseball fans. Heavily favored Athletics teams lost the World Series in both 1988, to the Los Angeles Dodgers, and in 1990, to the Cincinnati Reds. The latter was a shocking four-game sweep reminiscent of the A's loss to the Boston Braves 76 years earlier. The team began declining, winning the AL West championship in 1992 (but losing to Toronto in the ALCS), then finishing last in 1993.

The "Moneyball" years (1996–2004)

[edit]

In 1995, the Raiders returned to Oakland after spending 12 years in Los Angeles; with this, the Coliseum underwent an $83 million facelift that altered the Coliseum significantly.[22] Walter Haas died in that same year, and the team was sold to San Francisco Bay Area real estate developers Steve Schott (third cousin to one-time Cincinnati Reds' owner Marge Schott), silent partner David Etheridge and Ken Hofmann, prior to the 1996 season. Once again, the Athletics' star players were traded or sold, as the new owners' goal was to cut payroll drastically. Many landed with the St. Louis Cardinals, including McGwire, Eckersley, and manager La Russa. In a turn of events eerily reminiscent of the A's Roger Maris trade 38 years before, Mark McGwire celebrated his first full season with the Cardinals by setting a new major league home run record.

The Schott-Hofmann ownership allocated resources to building and maintaining a strong minor league system while almost always refusing to pay the going rate to keep star players on the team once they become free agents. Perhaps as a result, at the turn of the 21st century, the A's were a team that usually finished at or near the top of the AL West Division, but could not advance beyond the first round of the playoffs. The Athletics made the playoffs for four straight years, from 2000 to 2003, but lost their first round (best three-out-of-five) series in each case, 3 games to 2. In two of those years (2001 against the Yankees and 2003 against the Red Sox), the Athletics won the first two games of the series, only to lose the next three straight. In 2001, Oakland became the first team to lose a best-of-five series after winning both of the first two games on the road. In 2004, the A's missed the playoffs altogether, losing the final series of the season—and the divisional title—to the Anaheim Angels by one game.

This period in Oakland history featured splendid performances from a trio of young starting pitchers: right-hander Tim Hudson and left-handers Mark Mulder and Barry Zito. Between 1999 and 2006, the so-called "Big Three" helped the Athletics to emerge into a perennial powerhouse in the American League West, combining for a collective record of 261–131. They gave the Athletics a 1–2–3 punch to add to talented infielders and potent hitters, such as first baseman Jason Giambi, shortstop Miguel Tejada, and third baseman Eric Chavez. Giambi was named American League MVP in 2000, and Tejada won an MVP Award of his own in 2002, a year which also saw Zito win 23 games and the Cy Young Award.

On May 29, 2000, Randy Velarde achieved an unassisted triple play against the Yankees. In the sixth, second baseman Velarde caught Shane Spencer's line drive, tagged Jorge Posada running from first to second, and stepped on second before Tino Martinez could return. (Velarde had also pulled off an unassisted triple play during a spring training game that year). This was only the 11th unassisted triple play in the history of Major League Baseball.

The general manager of the Athletics, Billy Beane, has become notable due to Michael Lewis's portrayal of Beane's novel approach to business decisions and scouting, referred to as Moneyball, both the title of the book, and hence the school of baseball business management. The Athletics organization began redefining the way that major league baseball teams evaluate player talent. They began filling their system with players who did not possess traditionally valued baseball "tools" of throwing, fielding, hitting, hitting for power and running. Instead, they drafted for unconventional statistical prowess: on-base percentage for hitters (rather than batting average) and strikeout/walk ratios for pitchers (rather than velocity). These undervalued stats came cheaply. With the sixth-lowest payroll in baseball in 2002, the Oakland Athletics won an American League best 103 games. They spent $41 million that season, while the Yankees, who also won 103 games, spent $126 million. The Athletics have continually succeeded at winning, and defying market economics, keeping their payroll near the bottom of the league. For example, after the 2004 season, in which the A's placed second in their division, Beane shocked many by breaking up the Big Three, trading Tim Hudson to the Atlanta Braves and Mark Mulder to the St. Louis Cardinals. To many, the trades appeared bizarre, in that the two pitchers were seen to be at or near the top of their game; however, the decision was perfectly in line with Beane's business model as outlined in Moneyball. The Mulder trade, to many experts' surprise, turned into a steal for the Athletics, as little-known starter Dan Haren ended up pitching far better for Oakland than Mulder did for St. Louis.

Also during this time, the Athletics won an American League record 20 games in a row, from August 13 to September 4, 2002. The last three games were won in dramatic fashion, each victory coming in the bottom of the ninth inning. Win number 20 was notable because the A's, with Tim Hudson pitching, jumped to an 11–0 lead against the AL-cellar dwelling Kansas City Royals, only to slowly give up 11 unanswered runs to lose the lead. Then, Scott Hatteberg, enduring criticism as Jason Giambi's replacement, hit a pinch-hit home run off Royals closer Jason Grimsley in the bottom of the 9th inning to win 12–11. The streak was snapped two nights later in Minneapolis, the A's losing 6–0 to the Minnesota Twins. The Major League record for consecutive games without a loss is 26, set by the NL's New York Giants in 1916. There was a tie game embedded in that streak (ties were not uncommon in the days before stadium lights) and the record for consecutive wins with no ties is 22, held by the Cleveland Indians in 2017.

The Wolff era (2005–2016)

[edit]2005

[edit]On March 30, 2005, the Athletics were sold to a group fronted by real estate developer Lewis Wolff, although the majority owner is John J. Fisher, son of The Gap, Inc.'s founder. Wolff, though a Los Angeles businessman, had successfully developed many real estate projects in and around San Jose. The previous ownership had retained Wolff to help them find an adequate parcel on which to construct a new stadium. Because of Wolff's background, rumors that he wanted to move the team to San Jose surfaced periodically upon his purchase of the team. However, any such plans were always complicated by the claims of the cross-bay San Francisco Giants that they own the territorial rights to San Jose and Santa Clara County.

In 2005, many pundits picked the Athletics to finish last as a result of Beane's dismantling of the Big Three. At first, the experts appeared vindicated, as the A's were mired in last place on May 31 with a 19–32 (.373) win–loss record. After that the team began to gel, playing at a .622 clip for the remainder of the season, eventually finishing 88–74 (.543), seven games behind the newly renamed Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim and for many weeks seriously contending for the AL West crown.

Pitcher Huston Street was voted the AL Rookie of the Year in 2005, the second year in a row an Athletic won that award, shortstop Bobby Crosby having won in 2004. For the fifth straight season, third baseman Eric Chavez won the AL Gold Glove Award at that position.

2006

[edit]

The 2006 season brought the A's back to the postseason after a three-year absence. After finishing the season at 93–69, four games ahead of the Angels, the A's were considered the underdog against the highly favored Minnesota Twins. The A's swept the series 3–0 however, despite having to start on the road and losing second baseman Mark Ellis, who sustained a broken finger after getting hit by a pitch in the second game. Their victory was short-lived though, as the A's were swept 4–0 by the Detroit Tigers. Manager Ken Macha was fired by Billy Beane on October 16, four days after their loss in the 2006 American League Championship Series. Beane cited a disconnect between him and his players as well as a general unhappiness among the team as the reason for his sudden departure.[23]

Macha was replaced by bench coach and former major league catcher Bob Geren. Following the 2006 season, the A's also lost ace Barry Zito to the Giants due to free agency. They also lost their DH and MVP candidate Frank Thomas to free agency but filled his role with Mike Piazza for 2007. Piazza, a lifetime National League player, agreed to become a full-time DH for the first time in his career.

2007

[edit]The 2007 season was a disappointing season for the A's as they suffered from injuries to several key players Rich Harden, Huston Street, Eric Chavez, and Mike Piazza. For the first time since the 1998 season, the A's finished with a losing record.

The Athletics signed international free agent Michael Inoa to the largest bonus in team and international free agent history.

2008

[edit]The 2008 off-season started with controversy, as the A's traded ace pitcher Dan Haren to the Arizona Diamondbacks for prospects. This would be followed by trades of outfielder Nick Swisher, who was considered to be a fan-favorite, to the Chicago White Sox, and another fan-favorite Mark Kotsay (also outfielder) to the Atlanta Braves. The trades, especially the first two, caused a lot of anger among fans and the media. The A's were considered to be a "rebuilding" team and were expected to be among the bottom-feeders of MLB in the 2008 season. However, the A's performed well into late May, and even held first place in the AL West for a good amount of time, but a 2–7 roadtrip in mid-May allowed the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim to take first place.

On April 24, just weeks after playing against them while on the Blue Jays, Frank Thomas re-signed with the A's, having been released by the Jays after a slow start. On July 8, the A's were involved in a blockbuster trade, dealing Rich Harden and Chad Gaudin to the Chicago Cubs for Sean Gallagher, Josh Donaldson, Eric Patterson, and Matt Murton. Then on July 17, the A's traded Joe Blanton to the Philadelphia Phillies for three minor leaguers. An 18–37 record for the months of July and August (including a 10-game losing streak) dropped the A's into third place, where they would finish the season. They ended 2008 with a disappointing 75–86 record.

Several players were acquired in the offseason trades (pitchers Dana Eveland and Greg Smith from the Dan Haren trade, outfielder Ryan Sweeney from the Swisher trade and reliever Joey Devine from the Mark Kotsay trade). Carlos González and Gio González (no relation) from the Haren and Swisher trades, respectively, also performed well for the Triple-A Sacramento River Cats. It is worth pointing out that Haren, Swisher, and Kotsay have all played well in their new teams. Kotsay himself had a game-winning RBI as a pinch-hitter, against his former team on May 16 in Game 1 of an interleague series between the A's and Braves.

2009

[edit]In the 2009 offseason, the A's traded promising young star OF Carlos González, closer Huston Street and starting pitcher Greg Smith for Matt Holliday of the Colorado Rockies. On January 6, 2009, Jason Giambi signed a one-year, $4.6 million contract with a 2nd year option. Giambi said he was glad to be back as he put on his old number 16. Also signed were infielders Orlando Cabrera of the Chicago White Sox and Nomar Garciaparra of the Los Angeles Dodgers. The first half of the season the team played relatively poor, but finished the second half strong, yet still posting a losing record. Holliday was dealt to the St. Louis Cardinals for prospects and Giambi was released in August after spending time on the DL.

On December 22, 2009, Sports Illustrated named general manager Billy Beane as number 10 on its list of the Top 10 GMs/Executives of the Decade (in all sports).[24]

2010

[edit]The offseason was busy from the start. The team dealt the key-player from the Holliday trade, Brett Wallace, to the Toronto Blue Jays for OF Michael Taylor. After missing all of the 2009 season, Ben Sheets signed a 1-year deal. The team had a decent spring, posting a better record than other AL West teams. To begin the regular season, the team had 2 walk-off wins.

On May 9, 42 years almost to the day after Catfish Hunter, A's pitcher Dallas Braden pitched a perfect game, the 19th in Major League history, in a 4–0 victory over the Tampa Bay Rays at the Coliseum. The next homestand was a week-long celebration of the feat, with a commemorative graphic placed on the outfield wall on May 17.

Oakland finished the 2010 season with an 81–81 record; 2nd in the division, 9 games behind Texas, and 1 game ahead of Los Angeles.

2011

[edit]Oakland finished the 2011 season with a 74–88 record; 3rd in the division, 22 games behind Texas. Pitcher Rich Harden returned on a one-year deal. Hideki Matsui was signed as a DH on a one-year deal. Vin Mazarro was traded to the Royals for David DeJesus. Travis Buck, Jack Cust, and Edwin Encarnación were lost to the Indians, Mariners, and Blue Jays (respectively). Encarnacion was later claimed off waivers. Rajai Davis was traded to Toronto for two pitchers. Eric Chavez was lost to the Yankees as a free agent.

2012

[edit]After an offseason that saw All Star pitchers Gio González, Trevor Cahill, and Andrew Bailey traded away, the A's entered the 2012 season with low expectations. This season was Bob Melvin's first full season as the A's manager. During the trading period, the A's had traded fan-favorite catcher Kurt Suzuki to the Washington Nationals for cash considerations. The A's also traded relief pitcher Fautino de los Santos to the Milwaukee Brewers for catcher George Kottaras. On August 15, veteran starting pitcher Bartolo Colón received a 50-game suspension after testing positive for performing-enhancing drugs. On September 5, veteran pitcher Brandon McCarthy was struck in the head by a line drive off of the bat of Erick Aybar ending his 2012 season. The A's entered the last month of the season with an all-rookie starting rotation, but by the end of the month, they had pulled within 2 games of the Texas Rangers for the AL West lead, setting the stage for a season ending, 3-game series that would decide the winner of the 2012 division title. The A's swept the series, culminating in 12–5 victory which saw the A's come back from a 4-run deficit to clinch the AL West for the first time since 2006. The A's ended the regular season with a record of 94–68, leading the Major Leagues in walk-off wins, with 14 in the regular season, and one in Game 4 of the American League Division Series. The A's lost the ALDS to the eventual American League Champion Detroit Tigers in 5 games.

Bob Melvin was awarded the 2012 AL Manager of the Year award, and outfielder Josh Reddick was awarded a Gold Glove, becoming the first A's outfielder since 1985 to do so. Following the season shortstop Cliff Pennington was traded to the Arizona Diamondbacks for outfielder Chris Young, as part of a 3 team trade.

2013

[edit]In 2013, under manager Bob Melvin after going 96–66 and claiming their second straight division title over the heavily favored Texas Rangers and Los Angeles Angels, the Athletics lost Game 5 of the ALDS to Justin Verlander and the Detroit Tigers for the second straight season in their own ballpark. Josh Donaldson had an MVP-caliber season, with a .301 batting average 24 home runs, and 93 RBIs. Despite his age, Bartolo Colón was in contention for a Cy Young Award, going 18–6, with 117 strikeouts and a 2.65 ERA. During the regular season the A's saw the additions of former A's catcher Kurt Suzuki from the Washington Nationals, Alberto Callaspo from the Los Angeles Angels, and Stephen Vogt off waivers from the Tampa Bay Rays.Grant Balfour broke the A's record for most consecutive saves and the A's saw the growth of young players like Jed Lowrie, Yoenis Céspedes, Josh Donaldson, and Sonny Gray. The A's would finish in the top 3 of the Major League Baseball in home runs and OPS. Even after the devastating loss to the Detroit Tigers, the A's retained most of their 2013 roster, only losing Colon and Balfour to free agency.

2014

[edit]The A's started out as a favorite to win the AL West again, and played up to that, having the best record in baseball at the All-Star break. To bolster their starting rotation, they acquired pitchers Jeff Samardzija and Jason Hammel from the Chicago Cubs for several top prospects on July 4, and later acquired Jon Lester from the Boston Red Sox at the July 31 non-waiver trade deadline for Yoenis Céspedes. However, without the big bat of Cespedes, poor production from All-Stars Josh Donaldson and Brandon Moss, and an injury to closer Sean Doolittle, they struggled in August and the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim caught up, sweeping them in a key 4-game series between the two teams. At the August 31 waiver trade deadline, the A's acquired first baseman Adam Dunn from the Chicago White Sox and cash considerations for a minor league player. Despite their struggles which continued into September, they made the playoffs on the last day of the season, and faced the Kansas City Royals in the Wild Card Game. While they carried a 7–3 lead going into the bottom of the 8th inning, they managed to relinquish it due to the Royals' baserunning skills coupled with ineffective pitching, allowing them to tie the game. They did regain the lead in the top of the 12th, but the Royals responded with 2 runs in the bottom of the inning, winning on a walk-off single by Salvador Pérez.

2015

[edit]In the off-season the A's started to rebuild with trading Josh Donaldson, Jeff Samardzija, Brandon Moss, and losing Jon Lester to free agency.

The A's ended 2015 with a disappointing 68–94 record that put them in last place in the AL West. This despite Sonny Gray emerging as an ace of the staff with a 2.73 ERA and 14 wins in 31 starts. Nevertheless, the team brought in future key pieces in Marcus Semien, Mark Canha and Chris Bassitt, all of whom would become integral to the A's success later in the decade.

The John J. Fisher years (2016–2024)

[edit]2016

[edit]Like in 2015, the A's were in last place with a 69–93 record, despite a breakout season from newcomer Khris Davis, whose 42 home runs began a three-year stretch of 40 home run seasons. New arrivals in Sean Manaea and Liam Hendriks later became key pieces on the pitching staff moving forward. In November 2016, after the season ended, Wolff sold his 10% stake in the team to John J. Fisher, who became the full owner of the team; Wolff is now the chairman emeritus.[25]

2017

[edit]For the third straight year, the A's were in last place with a 75–87 record. The A's traded away ace Sonny Gray to the New York Yankees midway through the season, but brought in struggling reliever Blake Treinen from the Washington Nationals. In addition, Matt Chapman was called up as the third baseman of the future.

The team won 10 of their last 14 games, and rookie Matt Olson hit 24 home runs in just 189 at bats, finishing 4th in AL Rookie of the Year voting.

2018

[edit]On April 21, Sean Manaea threw the Athletics franchise's 12th no-hitter, and their first since Dallas Braden in 2010.[26]

The A's surprised the American League by winning 97 games, and earned a trip to the postseason as a wild card team. Bob Melvin became the American League Manager of the Year for the third time in his coaching career.

2019

[edit]On May 7 versus the Cincinnati Reds at the RingCentral Coliseum, Mike Fiers threw the Athletics franchise's 13th no-hitter. It was the second no-hitter of his career, and the 300th no-hitter in MLB history. To bolster the pitching rotation, on July 14, the Athletics acquired RHP Homer Bailey from the Kansas City Royals in exchange for SS Kevin Merrell. On July 27, to improve on their lack-luster bullpen, the Athletics acquired LHP Jake Diekman for OF Dairon Blanco and RHP Ismael Aquino. For the second consecutive season, the A's won 97 games and a playoff berth, earning the right to host the Tampa Bay Rays in the American League Wild Card game at Oakland Coliseum on October 2, 2019.[27] The A's were 52–27 at home on the season.[28]

2020

[edit]The Athletics finished with a 36–24 record in the shortened 2020 Major League Baseball season. The A's beat the Chicago White Sox two games to one in the first round of the expanded MLB postseason to face the Houston Astros. The Athletics lost to the Astros three games to one in the Division Series.

2021

[edit]In 2021, the Athletics finished third the AL West with an 86–76 record, missing the playoffs for the first time since 2017. Following the season, longtime manager Bob Melvin left the organization to become the manager of the San Diego Padres.[29]

On May 11, 2021, Major League Baseball granted the Athletics permission to explore relocation, saying that the Oakland Coliseum "is not a viable option for the future vision of baseball".[30]

2022

[edit]Prior to the 2022 season, the Athletics traded several key players away or let them leave during free agency. These players included Olson, Chapman, Bassitt, Manaea, Canha, and Starling Marte. Because the team's future in Oakland began looking more uncertain, some observers suspected that the organization was tanking with the hopes of fielding a competitive team in a new city.[31]

The Athletics wound up having a disastrous 2022 season in which the team finished last in the AL West with a 60–102 record. It was the worst record in the American League and Oakland's worst record since 1979.

Relocation to Sacramento and Las Vegas

[edit]2023

[edit]In April 2023, the Athletics finalized plans to relocate to Las Vegas, purchasing a 49-acre plot on the site of the Wild Wild West Gambling Hall & Hotel near the Las Vegas Strip for the construction of a new ballpark, ending negotiations with the city of Oakland.[32][33] On May 9, 2023, the Athletics switched their planned location to the site of Tropicana Las Vegas, which was demolished in October to make room for a 33,000-seat retractable roof stadium.[34] By June 2023, the team's 33,000-seat ballpark was approved through the Nevada Legislature voting in favor of its bill SB1 and sent to the desk of Governor Joe Lombardo where he would sign it into law. After SB1's signing, the Athletics announced the relocation process to the Las Vegas area would begin with the team drafting an application for the move by June 21.[35][36][37] The team would submit its relocation application fully on August 21.[38]

The Athletics finished the 2023 season with a 50–112 record, the worst in the major leagues.

2024

[edit]On November 16, 2023, the Athletics received official approval from MLB to relocate to Las Vegas.[39] By April, the team officially announced that 2024 would be its final season in Oakland and would spend three seasons at West Sacramento's Sutter Health Park until their new ballpark in Las Vegas is complete.[40] The Athletics played their final game at both the Coliseum and in Oakland on September 26, 2024, winning 3–2 against the Texas Rangers in front of 46,889 fans. On September 29, 2024, the Athletics played their final game as an Oakland-based team, losing 6–4 against the Seattle Mariners on the road. The Athletics finished 69–93, fourth in the AL West.

On May 13, 2024, in a game between the Houston Astros and the Athletics, Jenny Cavnar and Julia Morales became the first two women to do the play-by-play on television for the same Major League Baseball game.[41]

Fan reaction

[edit]

The A's plan to relocate to Las Vegas has garnered an overwhelmingly negative reception from Bay Area fans, baseball writers, former executives, and even some current players, including Las Vegas natives Bryce Harper, Bryson Stott, and Paul Sewald.[b] Many have argued that Fisher's lack of spending on the team was a deliberate effort to sink the club and keep fans away from the Coliseum in order to sabotage negotiations in Oakland.[50][51] Others have opined that by many measures, such as public money available and market size, Oakland was actually offering the better stadium deal, and that the relocation was purely an effort for the A's to remain on revenue sharing with no other factors considered, as some commentators have speculated that Fisher was no longer able to afford his part of the Howard Terminal project.[42][52] Outside of Oakland, fan protests against the move took place at Oracle Park in San Francisco, Coors Field in Denver, Nationals Park in Washington D.C., and the 2023 MLB All-Star Game at T-Mobile Park in Seattle.[53][54][55][56] Many of Manfred's comments and actions during the process received backlash as well, with several commentators feeling that he was being disrespectful towards Oakland and ignoring the reality of the situation in order to support an owner who could not afford to keep the team in Oakland.[57][58][59] The Sell movement continued into the 2024 season, and some fans have also begun supporting the Oakland Ballers of the Pioneer League.

Uniforms

[edit]At the start of their tenure in Oakland, owner Charles O. Finley used the team's colors of what he termed "Kelly Green, Wedding Gown White and Fort Knox Gold", which was changed during the team's tenure in Kansas City. It was here that he began experimenting with dramatic uniforms to match these bright colors, such as gold sleeveless tops with green undershirts and gold pants. The uniform innovations increased after the team's move to Oakland, which came with the introduction of polyester pullover uniforms.

During their dynasty years in the 1970s, the A's had dozens of uniform combinations with jerseys and pants in all three team colors, and never wore the traditional gray on the road, instead wearing green or gold, which helped to contribute to their nickname of "The Swingin' A's". After the team's sale to the Haas family, the team changed its primary color to a more subdued forest green in 1982 and began a move back to more traditional uniforms.

The 2023 team wore home uniforms with "Athletics" spelled out in script writing and road uniforms with "Oakland" spelled out in script writing, with the cap logo consisting of the traditional "A" with "apostrophe-s". The home cap, which was also the team's road cap until 1992, is forest green with a gold bill and white lettering. This design was also the basis of their batting helmet, which is used both at home and on the road. The road cap, which initially debuted in 1993, is all-forest green. The first version had the white "A's" wordmark before it was changed to gold the following season. An all-forest green batting helmet was paired with this cap until 2008. In 2014, the "A's" wordmark returned to white but added gold trim.

From 1994 until 2013, the A's wore green alternate jerseys with the word "Athletics" in gold, for both road and home games.

During the 2000s, the Athletics introduced black as one of their colors. They began wearing a black alternate jersey with "Athletics" written in green. After a brief discontinuance, the A's brought back the black jersey, this time with "Athletics" written in white with gold highlights. The cap paired with this jersey is all-black, initially with the green and white-trimmed "A's" wordmark, before switching to a white and gold-trimmed "A's" wordmark. Commercially popular but rarely chosen as the alternate by players, the black uniform was retired in 2011 in favor of a gold alternate jersey.

The gold alternate has "A's" in green trimmed in white on the left chest. With the exception of several road games during the 2011 season, the Athletics' gold uniforms were used as the designated home alternates. A green version of their gold alternates was introduced for the 2014 season, serving as a replacement to the previous green alternates. The new green alternates featured the piping, "A's" and lettering in white with gold trim.

In 2018, as part of the franchise's 50th anniversary since the move to Oakland, the A's wore a kelly green alternate uniform with "Oakland" in white with gold trim, and was paired with an all-kelly green cap.[60] This set was later worn with an alternate kelly green helmet with gold visor. This uniform eventually supplanted the gold alternates by 2019, and in 2022, after the forest green alternate was retired, it became the team's only active alternate uniform.

The nickname "A's" has long been used interchangeably with "Athletics", dating to the team's early days when headline writers used it to shorten the name. From 1972 through 1980, the team name was officially "Oakland A's", although the Commissioner's Trophy, given out annually to the winner of baseball's World Series, still listed the team's name as the "Oakland Athletics" on the gold-plated pennant representing the Oakland franchise. According to Bill Libby's Book, Charlie O and the Angry A's, owner Charlie O. Finley banned the word "Athletics" from the club's name because he felt that name was too closely associated with former Philadelphia Athletics owner Connie Mack, and he wanted the name "Oakland A's" to become just as closely associated with him. The name also vaguely suggested the name of the old minor league Oakland Oaks, which were alternatively called the "Acorns". New owner Walter Haas restored the official name to "Athletics" in 1981, but retained the nickname "A's" for marketing. At first, the word "Athletics" was restored only to the club's logo, underneath the much larger stylized-"A" that had come to represent the team since the early days. By 1987, however, the word returned, in script lettering, to the front of the team's jerseys.

Prior to the mid-2010s, the A's had a long-standing tradition of wearing white cleats team-wide (in line with the standard MLB practice that required all uniformed team members to wear a base cleat color), which dated to the Finley ownership. Since the mid-2010s, however, MLB has gradually relaxed its shoe color rules, and several A's players began wearing cleats in non-white colors, such as Jed Lowrie's green cleats.

Ballpark history

[edit]The Oakland Coliseum—originally the Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum, and later named as Network Associates, McAfee, Overstock.com/O.co and RingCentral Coliseum—was built as a multi-purpose facility. Louisiana Superdome officials pursued negotiations with Oakland Athletics officials during the 1978–79 baseball offseason about moving the Oakland Athletics to their facility in New Orleans. The Oakland Athletics were unable to break their lease at the Coliseum, and remained in Oakland.[61]

After the Oakland Raiders Redskins moved to Los Angeles in 1982, many improvements were made to what was suddenly a baseball-only facility. The 1994 movie Angels in the Outfield was filmed in part at the Coliseum, filling in for Anaheim Stadium following the damage from the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

In 1995, the Raiders moved back to Oakland. The Coliseum was expanded to 63,026 seats. The bucolic view of the Oakland foothills that baseball spectators enjoyed was replaced with a jarring view of an outfield grandstand contemptuously referred to as "Mount Davis" after Raiders' owner Al Davis. Because construction was not finished by the start of the 1996 season, the Athletics were forced to play their first six-game homestand at 9,300-seat Cashman Field in Las Vegas, Nevada.[62]

Although official capacity was listed as 43,662 for baseball, seats were sometimes sold in Mount Davis, pushing actual capacity to nearly 60,000. The ready availability of tickets on game day made season tickets a tough sell, while crowds as high as 30,000 often seemed sparse in such a venue. On December 21, 2005, the Athletics announced that seats in the Coliseum's third deck would not be sold for the 2006 season, but would instead be covered with a tarp, and that tickets would no longer be sold in Mount Davis under any circumstances. That effectively reduced capacity to 34,077, making the Coliseum the lowest-capacity stadium in Major League Baseball. Beginning in 2008, sections 316–318 immediately behind home plate were the only third-deck sections open for A's games, which brought the total capacity to 35,067 until 2017, when new team president Dave Kaval took the tarps off of the upper deck, increasing capacity to 47,170. The Athletics were the last MLB team to share a stadium full-time with an NFL team, a situation that ended when the Raiders moved to Las Vegas in 2020.

The Oakland Athletics' spring training facility is Hohokam Stadium, in Mesa, Arizona. From 1982 to 2014, their spring training facility was Phoenix Municipal Stadium, in Phoenix, Arizona; they also spent time playing in Scottsdale, Arizona.[63][64]

Improvements to the Coliseum

[edit]

New areas

[edit]In 2017, the team created an outdoor plaza in the space between the Coliseum and Oracle Arena. The grassy area is open to all ticketed fans, and it features food trucks, seating and games like corn hole for every Athletics home game.[65][66] The following year, the team introduced The Treehouse, a 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) area open to all fans with two full-service bars, standing-room and lounge seating, numerous televisions with pre-game and postgame entertainment. The A's Stomping Ground transformed part of the Eastside Club and the area near the right-field flag poles into a fun and interactive space for kids and families. The inside section features a stage and video wall for interactive events, a digital experience that lets youngsters race their favorite Athletics players, replica team dugouts, a simulated hitting and pitching machine, foosball, and a photo booth. The outside area includes play areas, a grassy seating area, drink rails for parents, and picnic tables, a miniature baseball field and spiderweb play area.[67]

Premium spaces

[edit]The team added three new premium spaces, including The Terrace, Lounge Seats, and the Coppola Theater Boxes, to the Coliseum for the 2019 season. The new premium seating options offer fans a high-end game-day experience with luxury amenities. The team also added two new group spaces – the Budweiser Hero Deck and Golden Road Landing – to the Coliseum.[68]

Other additions

[edit]In addition, the tarps on the upper deck were removed; a modern version of the beloved mechanical Harvey the Rabbit to deliver the first pitch ball was re-introduced, while the playing surface at the Coliseum was renamed "Rickey Henderson Field". The team held the first free game in MLB history for 46,028 fans on April 17, 2018, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Athletics first game in Oakland.[69] The team tried a new concept in season ticketing in the A's Access plan that involved "general admission access to every home game with a set number of reserved-seat upgrades allotted", which was meant to replace previous attempts at subscription-based services that they tried with Ballpark Pass and Treehouse Pass.[70] On July 21, 2018, the Athletics set a Coliseum record for the largest attendance with a crowd of 56,310 when the team hosted to the San Francisco Giants.[70][71]

Prior stadium proposals

[edit]Oakland

[edit]Since the early 2000s, the Oakland A's had been in talks with Oakland and other Northern California cities about building a new baseball-only stadium. The team had said it wanted to remain in Oakland. A 2017 plan would have placed a new 35,000 seat A's stadium near Laney College and the Eastlake neighborhood on the site of the Peralta Community College District's administration buildings. The plan was announced by team president Dave Kaval in September 2017.[72] However, three months later, negotiations abruptly ended.[73] On November 28, 2018, the Oakland Athletics announced that the team had chosen to build its new 34,000-seat ballpark at the Howard Terminal site at the Port of Oakland. The team also announced its intent to purchase the Coliseum site and renovate it into a tech and housing hub, preserving Oakland Arena and reducing the Coliseum to a low-rise sports park as San Francisco did with Kezar Stadium.[74] In April 2023, the City of Oakland ended discussions with the Oakland Athletics organization after the announcement of a new ballpark in Las Vegas, amid widespread claims that the team was not negotiating in good faith and was using the proposed site in Oakland to leverage a better deal in Las Vegas instead of any real intention to stay within the city.[75]

Fremont

[edit]On November 7, 2006, the news media announced the Athletics would be leaving Oakland as early as 2010 for a new stadium in Fremont, confirmed the next day by the Fremont City Council. The plan was strongly supported by Fremont Mayor Bob Wasserman.[76] The team would have played in Cisco Field, a 32,000-seat, baseball-only facility.[77] The proposed ballpark would have been part of a larger "ballpark village" which would have included retail and residential development. On February 24, 2009, however, Lew Wolff released an open letter announcing the end of his efforts to relocate the A's to Fremont, citing "real and threatened" delays to the project.[78] The project faced opposition from some in the community who thought the relocation of the A's to Fremont would increase traffic problems in the city and decrease property values near the ballpark site.

San Jose

[edit]In 2009, the City of San Jose attempted to open negotiations with the team regarding a move to the city. Although land south of Diridon Station would be acquired by the city as a stadium site, the San Francisco Giants' claim on Santa Clara County as part of their home territory would have to be settled before any agreement could be made.[79]

By 2010, San Jose was "aggressively wooing" Oakland A's owner Lew Wolff, the city as the team's "best option", but Major League Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig said he would await a report on whether the team could move to the area, because of the Giants conflict.[80] In September 2010, 75 Silicon Valley CEOs drafted and signed a letter to Bud Selig urging a timely approval of the move to San Jose.[81] In May 2011, San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed sent a letter to Bud Selig asking the commissioner for a timetable of when he might decide whether the A's can pursue this new ballpark, but Selig did not respond.[82]

Selig addressed the San Jose issue via an online town hall forum held in July 2011, saying, "Well, the latest is, I have a small committee who has really assessed that whole situation, Oakland, San Francisco, and it is complex. You talk about complex situations; they have done a terrific job. I know there are some people who think it's taken too long and I understand that. I'm willing to accept that. But you make decisions like this; I've always said, you'd better be careful. Better to get it done right than to get it done fast. But we'll make a decision that's based on logic and reason at the proper time."[83]

On June 18, 2013, the City of San Jose filed suit against Selig, seeking the court's ruling that Major League Baseball may not prevent the Oakland A's from moving to San Jose.[84] Wolff criticized the lawsuit, stating he did not believe business disputes should be settled through legal action.[85]

Most of the city's claims were dismissed in October 2013, but a U.S. District Judge ruled that San Jose could move forward with its claim that MLB illegally interfered with a land agreement between the city and the A's. On January 15, 2015, a three-judge panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled unanimously that the claims were barred by baseball's antitrust exemption, established by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1922 and upheld in 1953 and 1972. San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo commented that the city would seek a ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court.[86] On October 5, 2015, the United States Supreme Court rejected San Jose's case.[87]

Rivalries

[edit]San Francisco Giants

[edit]The Bay Bridge Series was the name of a series of games played between (and the rivalry of) the Oakland A's and San Francisco Giants of the National League. The series took its name from the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge which links the cities of Oakland and San Francisco. Although competitive, the regional rivalry between the A's and Giants was considered a friendly one with mostly mutual companionship between the fans, as opposed to White Sox–Cubs, or Yankees–Mets games where animosity ran high. Hats displaying both teams on the cap were sold from vendors at the games, and once in a while the teams both dressed in original team uniforms from the early era of baseball. The series was also occasionally referred to as the "BART Series" for the Bay Area Rapid Transit system that links Oakland to San Francisco. However, the name "BART Series" had never been popular beyond a small selection of history books and national broadcasters and had fallen out of favor. Bay Area locals almost exclusively referred to the rivalry as the "Battle of the Bay".[88]

Originally, the term described a series of exhibition games played between the two clubs after the conclusion of spring training, immediately prior to the start of the regular season. It was first used to refer to the 1989 World Series in which the Athletics won their most recent championship and the first time the teams had met since they moved to the San Francisco Bay Area (and the first time they had met since the A's also defeated the Giants in the 1913 World Series). Since the commencement of interleague play, it also referred to games played between the teams during the regular season since 1997. In its existence, the Athletics had won 76 regular season games, and the Giants had won 72 contests.[89]

The A's also had edges on the Giants in terms of overall postseason appearances (21–13), division titles (17–10) and World Series titles (4–3) since both teams moved to the Bay Area, even though the Giants franchise moved there a decade earlier than the A's did.

On March 24, 2018, the Oakland A's announced that for the Sunday, March 25, 2018, exhibition game against the San Francisco Giants, A's fans would be charged $30 for parking and Giants fans would be charged $50. However, the A's stated that Giants fans could receive $20 off if they shout "Go A's" at the parking gates.[90]

In 2018, the Athletics and Giants started battling for a "Bay Bridge" Trophy[91] made from steel taken from the old east span of the Bay Bridge, which was taken down after the new span was opened in 2013.[92][93] The A's won the inaugural season with the trophy, allowing them to place their logo atop its Bay Bridge stand.[94] When the A's left Oakland, the Giants had won the trophy 4 times, to the A's 3.

Los Angeles Angels

[edit]The A's had held a rivalry with the Los Angeles Angels since their relocation to California in 1968, and the charter membership of both teams in the AL West in 1969. The A's and Angels had often competed for the division title.[95] The peak of the rivalry was during the early part of the millennium as both teams were perennial contenders. During the 2002 season, the A's famous "Moneyball" tactics led them to a league record 20-game winning streak, knocking the Angels out of the first seed in the division. The A's finished 4 games ahead while the Angels secured the Wild Card berth.[96] Despite the 103-win season for Oakland, they lost to the underdog Minnesota Twins in the ALDS. The Angels beat the heavily favored New York Yankees, then beat the Twins, and then won the 2002 World Series. During the 2004 season, the teams were tied for wins headed into the final week of September with the last three games being played in Oakland against the Angels.[97] Both teams were battling to secure the division championship. Oakland lost two of the three games to the Angels, and they were eliminated from the playoff hunt. The Angels were swept in the playoffs by the eventual champion Boston Red Sox.[98] While in Oakland, the Athletics lead the series 492–414. The two teams never met in the postseason.

Achievements

[edit]Awards

[edit]- The Oakland Athletics give out an award named the Catfish Hunter Award since 2004 for the most inspirational Oakland Athletic.

Hall of Famers

[edit]| Oakland Athletics Hall of Famers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||

|

Ford C. Frick Award recipients

[edit]| Oakland Athletics Ford C. Frick Award recipients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||

|

Retired numbers

[edit]The Oakland Athletics had retired six numbers; additionally, Walter A. Haas, Jr., owner of the team from 1980 until his death in 1995, was honored by the retirement of the letter "A". Of the six players with retired numbers, five were retired for their play with the Oakland Athletics and one, 42, was universally retired by Major League Baseball when they honored the 50th anniversary of Jackie Robinson's breaking the color barrier. No A's player from the Philadelphia era had his number retired by the organization. Though Jackson and Hunter played small portions of their careers in Kansas City, no player that played the majority of his years in the Kansas City era had his number retired either. The Oakland A's had retired only the numbers of Hall-of-Famers who played large portions of their careers in Oakland. The Oakland Athletics had all of the numbers of the Hall-of-Fame players from the Philadelphia Athletics displayed at their stadium, as well as all of the years that the Philadelphia Athletics won World Championships (1910, 1911, 1913, 1929, and 1930). Dave Stewart was about to have his #34 jersey retired by the Oakland Athletics in 2020, but the ceremony was postponed until further notice, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Questions were raised if there would be a formal ceremony after no news about a reschedule happened in 2021 before it was announced in April 2022 that Stewart would have his jersey retired on September 11, 2022.[99][100] Stewart broke the A's tradition in that his number was a re-retirement, as well as his not being in the Hall of Fame.

|

Oakland Athletics Hall of Fame

[edit]On August 14, 2018, the team publicly announced the creation of a team Hall of Fame, complete with the first seven names to be inducted.[101] On September 5, the Oakland Athletics held a ceremony to induct seven members into the inaugural class. Each member was honored with an unveiling of a painting in their likeness and a bright green jacket. Hunter, who died in 1999, was represented by his widow, while Finley, who died in 1996, was represented by his son. Had the Oakland Athletics got a new stadium in Oakland, a physical site would have been designated for the Hall of Fame, as the Coliseum does not have enough space for a full-fledged exhibit.[102] In August 2021, it was announced that players Sal Bando, Eric Chavez, Joe Rudi, director of player development Keith Lieppman, and clubhouse manager Steve "Vuc" Vucinich would be part of the class of 2022; in November 2021, Ray Fosse, who had died the previous month, was posthumously inducted into the Hall of Fame.[103][104] The 2023 & 2024 classes were inducted in August of each respective year.[105][106]

| Bold | Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame |

|---|---|

†

|

Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame as an Athletic |

| Bold | Recipient of the Hall of Fame's Ford C. Frick Award |

| Oakland Athletics Hall of Fame | ||||

| Year | No. | Player | Position | Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 43 | Dennis Eckersley† | P | 1987–1995 |

| 32, 38, 34 | Rollie Fingers† | P | 1968–1976 | |

| 39, 35, 22, 24 | Rickey Henderson† | LF | 1979–1984 1989–1993 1994–1995 1998 | |

| 27 | Catfish Hunter | P | 1968–1974 | |

| 9, 44 | Reggie Jackson | RF | 1968–1975 1987 | |

| 34, 35 | Dave Stewart | P | 1986–1992 1995 | |

| — | Charlie Finley | Owner General Manager |

1968–1981 | |

| 2019 | 10, 11, 22, 42 | Tony La Russa | IF Manager |

1968–1971 1986–1995 |

| 14, 17, 21, 28, 35 | Vida Blue | P | 1969–1977 | |

| 19 | Bert "Campy" Campaneris | SS | 1968–1976 | |

| 25 | Mark McGwire | 1B | 1986–1997 | |

| — | Walter A. Haas, Jr. | Owner | 1981–1995 | |

| 2022 | 30, 3 | Eric Chavez | 3B | 1998–2010 |

| 6 | Sal Bando | 3B | 1968–1976 | |

| 45, 8, 36, 26 | Joe Rudi | LF / 1B | 1968–1976 1982 | |

| 10 | Ray Fosse | C Broadcaster |

1973–1975 1986–2021 | |

| — | Keith Lieppman | Director of Player Development | 1971–present | |

| — | Steve Vucinich | Clubhouse manager | 1968–present | |

| 2023 | 16 | Jason Giambi | LF / 1B | 1995–2001 2009 |

| 5, 4 | Carney Lansford | 3B | 1983–1992 | |

| 24, 38, 18 | Gene Tenace | C / 1B | 1969–1976 | |

| — | Roy Steele | Public address announcer | 1968–2005 2007–2008 | |

| 2024 | 33 | Jose Canseco | RF / DH | 1985–1992 1997 |

| 36 | Terry Steinbach | C | 1986–1996 | |

| 4 | Miguel Tejada | SS | 1997–2003 | |

| 23 | Dick Williams† | Manager | 1971–1973 | |

| — | Bill King | Broadcaster | 1981–2005 | |

Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

[edit]

17 members of the Athletics organization have been honored with induction into the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame.

| Athletics in the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame | ||||

| No. | Player | Position | Tenure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Dusty Baker | OF | 1985–1986 | |

| 14, 17, 21, 28, 35 | Vida Blue | P | 1969–1977 | |

| 19 | Bert "Campy" Campaneris | SS | 1964–1976 | |

| 12 | Orlando Cepeda | 1B | 1972 | Elected mainly on his performance with San Francisco Giants |

| 4, 6, 10, 14 | Sam Chapman | CF | 1938–1941 1945–1951 |

Born and raised in Tiburon, California |

| 43 | Dennis Eckersley | P | 1987–1995 | Grew up in Fremont, California |

| 32, 34, 38 | Rollie Fingers | P | 1968–1976 | |

| — | Walter A. Haas, Jr. | Owner | 1981–1995 | Grew up in San Francisco, California, attended UC Berkeley |

| 24 | Rickey Henderson | LF | 1979–1984 1989–1993 1994–1995 1998 |

Raised in Oakland, California |

| 27 | Catfish Hunter | P | 1965–1974 | |

| 9, 31, 44 | Reggie Jackson | RF | 1968–1975 1987 |

|

| 1 | Eddie Joost | SS Manager |

1947–1954 1954 |

Born and raised in San Francisco, California |

| 10, 11, 22, 29, 42 | Tony La Russa | IF Manager |

1963 1968–1971 1986–1995 |

|

| 1, 4 | Billy Martin | 2B Manager |

1957 1980–1982 |

Elected mainly on his performance with New York Yankees, Born in Berkeley, California |

| 44 | Willie McCovey | 1B | 1976 | Elected mainly on his performance with San Francisco Giants |

| 8 | Joe Morgan | 2B | 1984 | Elected mainly on his performance with Cincinnati Reds, raised in Oakland, California |

| 19 | Dave Righetti | P | 1994 | Born and raised in San Jose, California |

| 34 | Dave Stewart | P | 1986–1992 1995 |

Born and raised in Oakland, California |

Team captains

[edit]- 6 Sal Bando, 3B, 1969–1976

Radio and television

[edit]As of the 2020 season, the Oakland Athletics had 14 radio homes.[107] The Oakland Athletics' flagship radio station was KNEW and the team had a free live 24/7 exclusive A's station branded as A's Cast to stream the radio broadcast within the Oakland Athletics market and other A's programming via iHeartRadio.[108] Going into the 2020 season, the Oakland Athletics had a deal with TuneIn for A's Cast and no flagship radio station in the Bay Area but changed their plans due to the COVID-19 pandemic keeping fans from attending games.[109] The announcing team featured Ken Korach and Vince Cotroneo.

Television coverage was exclusively on NBC Sports California. Some A's games aired on an alternate feed of NBCS, called NBCS Plus, if the main channel showed a Sacramento Kings or San Jose Sharks game at the same time. On TV, Jenny Cavnar covered play-by-play, and Dallas Braden provided color commentary. Some games would feature Chris Caray on play-by-play; Caray is a fourth-generation baseball announcer that included great-grandfather Harry Caray, grandfather Skip Caray, and father Chip Caray.

In popular culture

[edit]The 2003 Michael Lewis book Moneyball chronicles the 2002 Oakland Athletics season, with a focus on Billy Beane's economic approach to managing the organization under significant financial constraints. Beginning in June 2003, the book remained on The New York Times Best Seller list for 18 consecutive weeks, peaking at number 2.[110][111] In 2011, Columbia Pictures released a film adaptation based on Lewis' book, which featured Brad Pitt playing the role of Beane. On September 19, 2011, the U.S. premiere of Moneyball was held at the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, which featured a green carpet for attendees to walk, rather than the traditional red carpet.[112]

The blog that spawned the full-fledged popular sports blog site SBNation was dedicated to the Oakland Athletics.[113][114]

Eric Shaun Lynch, a former member of The Howard Stern Show's Wack Pack who went by the name "Eric the Actor" (and previously, "Eric the Midget"), was a huge fan of the Oakland Athletics and would occasionally talk about them on Stern's show. Following his death in September 2014, the team broadcasters offered a tribute by using Lynch's signature sign off "bye for now" at the end of an Oakland Athletics game broadcast. During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, when American baseball teams were using cutouts of fans to show solidarity in their absence, the Oakland Athletics placed a cutout of Lynch among other cutouts of the team's fans.

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "About Stomper". Athletics.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ Clair, Michael (March 17, 2017). "Why do the A's wear green? You can thank Charlie Finley". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

Before Finley came on board, the then-Kansas City A's wore baseball's standard blue-and-red combination. In 1963, that all changed as Finley outfitted the team in glorious gold (Finley said it was the same shade the United States Naval Academy used) and kelly green for the very first time.

- ^ Clair, Michael (February 27, 2021). "The best baseball caps ever, by team". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

How many big league teams do you know that wear green and yellow, the most fantastic color scheme in the world? Exactly: Only one.

- ^ "The Bonham Daily Favorite – Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "Athletics sign lease for Louisville move". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. January 7, 1964. p. 8.

- ^ "Finley Signs Contract to Transfer Athletics to Louisville". The New York Times. January 6, 1964. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018. Retrieved April 29, 2008.

- ^ "Finley hears AL message; sign contract or go away". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. January 17, 1964. p. 12.

- ^ Castrovince, Anthony (January 9, 2022). "Cities that almost had an MLB team". MLB.com. Retrieved January 20, 2022.