Xenophon

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Xenophon of Athens | |

|---|---|

Bust statue of Xenophon | |

| Born | c. 430 BC[1] |

| Died | Probably 354 or 355 BC[2] (aged c. 74 or 75) |

| Occupations |

|

| Notable work | |

| Children | Gryllus and Diodorus |

| Parent | Gryllus |

Xenophon of Athens (/ˈzɛnəfən, ˈziːnə-, -ˌfɒn/; Ancient Greek: Ξενοφῶν, romanized: Xenophôn [ksenopʰɔ̂ːn]; c. 430[1] – probably 355 or 354 BC[2]) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been part of Cyrus's attempt to seize control of the Achaemenid Empire. As the military historian Theodore Ayrault Dodge wrote, "the centuries since have devised nothing to surpass the genius of this warrior".[4] Xenophon established precedents for many logistical operations and was among the first to describe strategic flanking maneuvers and feints in combat.

For at least two millennia, it has been debated whether or not Xenophon was first and foremost a general, historian, or philosopher. For the majority of time in the past two millennia, Xenophon was recognized as a philosopher. Quintilian in The Orator's Education discusses the most prominent historians, orators and philosophers as examples of eloquence and recognizes Xenophon's historical work, but ultimately places Xenophon next to Plato as a philosopher. Today, Xenophon is recognized as one of the greatest writers of antiquity.[5] Xenophon's works span multiple genres and are written in plain Attic Greek, which is why they have often been used in translation exercises for contemporary students of the Ancient Greek language. In the Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes Laërtius observed that Xenophon was known as the "Attic Muse" because of the sweetness of his diction.[6]

Despite being born an Athenian citizen, Xenophon came to be associated with Sparta, the traditional opponent of Athens. Much of what is known today about the Spartan society comes from Xenophon's royal biography of the Spartan king Agesilaus and the Constitution of the Lacedaemonians. The sub-satrap Mania is primarily known through Xenophon's writings. Xenophon's Anabasis recounts his adventures with the Ten Thousand while in the service of Cyrus the Younger, Cyrus's failed campaign to claim the Persian throne from Artaxerxes II of Persia, and the return of Greek mercenaries after Cyrus's death in the Battle of Cunaxa.

Xenophon wrote Cyropaedia, outlining both military and political methods used by Cyrus the Great to conquer the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BC. Anabasis and Cyropaedia inspired Alexander the Great and other Greeks to conquer Babylon and the Achaemenid Empire in 331 BC.[7][page needed] The Hellenica continues directly from the final sentence of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War covering the last seven years of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) and the subsequent forty-two years (404–362 BC) ending with the Second Battle of Mantinea.

Life

[edit]Early years

[edit]Xenophon was born c. 430 BC, in the deme Erchia of Athens. Xenophon's father, Gryllus, was a member of a wealthy equestrian family.[8] Accounts of events in Hellenica suggest that Xenophon personally witnessed the return of Alcibiades in 407 BC, the trial of the generals in 406 BC, and the overthrow of the Thirty Tyrants in 403 BC.

Personally invited by Proxenus of Beotia (Anabasis 3.1.9), one of the captains in Cyrus's mercenary army, Xenophon, sailed to Ephesus to meet Cyrus the Younger and participate in Cyrus's military campaign against Tissaphernes, the Persian satrap of Ionia. Xenophon describes his life in 401 BC and 400 BC in the memoir Anabasis.

Anabasis

[edit]

Written years after the events it recounts, Xenophon's book Anabasis (Greek: ἀνάβασις, literally "going up")[9] is his record of the expedition of Cyrus and the Greek mercenaries' journey to home.[10] Xenophon writes that he asked Socrates for advice on whether to go with Cyrus and that Socrates referred him to the Pythia. Xenophon's query to the oracle, however, was not whether or not to accept Cyrus' invitation, but "to which of the gods he must pray and do sacrifice, so that he might best accomplish his intended journey and return in safety, with good fortune". The oracle answered his question and told him which gods to pray and sacrifice to. When Xenophon returned to Athens and told Socrates of the oracle's advice, Socrates chastised him for asking so disingenuous a question (Anabasis 3.1.5–7).

Under the pretext of fighting Tissaphernes, the Persian satrap of Ionia, Cyrus assembled a massive army composed of native Persian soldiers and Greeks. Prior to waging war against Artaxerxes, Cyrus proposed that the enemy was the Pisidians, and so the Greeks were unaware that they were to battle against the larger army of King Artaxerxes II (Anabasis 1.1.8–11). At Tarsus, the soldiers became aware of Cyrus's plans to depose the king and, as a result, refused to continue (Anabasis 1.3.1). However, Clearchus, a Spartan general, convinced the Greeks to continue with the expedition. The army of Cyrus met the army of Artaxerxes II in the Battle of Cunaxa. Cyrus was killed in the battle (Anabasis 1.8.27–1.9.1). Shortly thereafter, Clearchus was invited by Tissaphernes to a feast, where, alongside four other generals and many captains, including Xenophon's friend Proxenus, he was captured and executed (Anabasis 2.5.31–32).

Return

[edit]

The mercenaries, known as the Ten Thousand, had no leadership in territory near Mesopotamia. They elected new leaders, including Xenophon himself. Dodge says of Xenophon's generalship, "Xenophon is the father of the system of retreat [...] He reduced its management to a perfect method."[11]

Xenophon and his men initially had to deal with volleys by a minor force of harassing Persian missile cavalry. One night, Xenophon formed a body of archers and light cavalry. When the Persian cavalry arrived the next day, now firing within several yards, Xenophon unleashed his new cavalry, killing many and routing the rest.[12] Tissaphernes pursued Xenophon, and when the Greeks reached the Great Zab river, one of the men devised a plan: goats, cows, sheep, and donkeys were to be slaughtered and their bodies stuffed with hay, sewn up, laid across the river, and covered with dirt so as not to be slippery and be used as a bridge to cross the river. This plan was discarded as impractical.

Dodge notes, "On this retreat also was first shown the necessary, if cruel, means of arresting a pursuing enemy by the systematic devastation of the country traversed and the destruction of its villages to deprive him of food and shelter. And Xenophon is moreover the first who established in rear of the phalanx a reserve from which he could at will feed weak parts of his line. This was a superb first conception."[13]

Conflicts

[edit]

The Ten Thousand eventually made their way into the land of the Carduchians, a wild tribe inhabiting the mountains of modern southeastern Turkey. "Once the Great King had sent into their country an army of 120,000 men, to subdue them, but of all that great host not one had ever seen his home again."[15] The Ten Thousand were shot at with stones and arrows for several days before they reached a defile where the main Carduchian host sat. Xenophon had 8,000 men feint and marched the other 2,000 to a pass revealed by a prisoner under the cover of a rainstorm, and at daylight, they pushed in.[16]

After the fighting, the Greeks went to the northern foothills of the mountains at the Centrites River, later finding a Persian force blocking the route north. Xenophon's scouts found another ford, but the Persians blocked this as well. Xenophon sent a small force back toward the other ford, causing the Persians to detach a major part of their force parallel. Xenophon overwhelmed the force at his ford.

Winter has arrived as the Greeks marched through Armenia "absolutely unprovided with clothing suitable for such weather".[17] The Greeks decided to attack a wooden castle known to have had storage. The castle was stationed on a hill surrounded by forest. Xenophon ordered small parties of his men to appear on the hill road, and when the defenders fired, one soldier would leap into the trees. Then, "the other men followed his example [...] When the stones were almost exhausted, the soldiers raced one another over the exposed part of the road", storming the fortress with most of the garrison now neutralized.[18]

Soon after, Xenophon's men reached Trapezus on the coast of the Black Sea (Anabasis 4.8.22). Before their departure, the Greeks made an alliance with the locals and fought one last battle against the Colchians, vassals of the Persians. Xenophon ordered his men to deploy the line extremely thin so as to overlap the enemy. The Colchians divided their army to check the Greek deployment, opening a gap in their line through which Xenophon rushed in his reserves.[19] They then made their way westward back to Greek territory via Chrysopolis (Anabasis 6.3.16). Once there, they helped Seuthes II make himself king of Thrace before being recruited into the army of the Spartan general Thimbron (whom Xenophon refers to as Thibron).

Xenophon's conduct of the retreat caused Dodge to name the Athenian knight the greatest general that preceded Alexander the Great.[20]

Life after Anabasis

[edit]Xenophon's Anabasis ends in 399 BC in the city of Pergamon with the arrival of the Spartan commander Thimbron. Thimbron's campaign is described in Hellenica.[21] In the describtors, after capturing Teuthrania and Halisarna, the Greeks led by Thimbron lay siege to Larissa. Failing to capture Larissa, the Greeks fall back to Caria. As a result, the ephors of Sparta recall Thimbron and send Dercylidas to lead the Greek army. After facing the court at Sparta, Thimbron is banished. Xenophon describes Dercylidas as a significantly more experienced commander than Thimbron.

Led by Dercylidas, Xenophon and the Greek army march to Aeolis and capture nine cities in 8 days, including Larissa, Hamaxitus, and Kolonai.[22] The Persians negotiated a temporary truce, and the Greek army retired for a winter camp at Byzantium. In 398 BC, Xenophon captured the city of Lampsacus. The Spartan ephors officially cleared the Ten Thousand of any previous wrongdoing (the Ten Thousand were likely a part of the investigation of Thimbron's failure at Larissa) and integrated the Ten Thousand into Dercylidas' army. Hellenica mentions the response of the commander of the Ten Thousand, "But men of Lacedaemon, we are the same men now as we were last year; but the commander now is one man (Dercylidas), and in the past was another (Thimbron). Therefore you are at once able to judge for yourselves the reason why we are not at fault now, although we were then."[22]

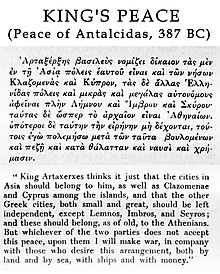

In 397 BC, Dercylidas' force mirrored the movement of Tissaphernes' and Pharnabazus' forces near Ephesus but did not engage in battle. The Persian army retreated to Tralles and the Greeks to Leucophrys. Dercylidas proposed the new terms of truce to Tissaphernes and Pharnabazus and the three parties submitted the truce proposal to Sparta and the Persian king for ratification. Under Dercylidas' proposal, the Persians abandoned claims to independent Greek cities in Ionia, and the Spartans withdrew the army.

In 396 BC, the newly appointed Spartan king, Agesilaus, arrived at Ephesus and assumed command of the army from Dercylidas. Xenophon joined Agesilaus' campaign for the Ionian Greece independence of 396–394 BC. In 394 BC, Agesilaus' army returned to Greece, taking the route of the Persian invasion eighty years earlier and fought in the Battle of Coronea. Athens banished Xenophon for fighting on the Spartan side. Xenophon probably followed Agesilaus' march to Sparta in 394 BC and finished his military journey after seven years. Xenophon received an estate in Scillus where he spent the next twenty-three years. In 371 BC, after the Battle of Leuctra, the Elians confiscated Xenophon's estate, and, according to Diogenes Laërtius, Xenophon moved to Corinth.[23] Diogenes writes that Xenophon lived in Corinth until his death in 354 BC, at around the age of 74 or 75. Pausanias mentions Xenophon's tomb in Scillus.[24]

Political philosophy

[edit]Xenophon took a keen interest in political philosophy[25] and his work often examines leadership.

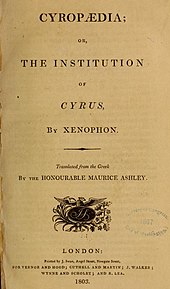

Cyropaedia

[edit]Relations between Medes and Persians in the Cyropaedia

[edit]

Xenophon wrote the Cyropaedia to outline his political and moral philosophy. He did this by endowing a fictional version of the boyhood of Cyrus the Great, founder of the first Persian Empire, with the qualities of what Xenophon considered the ideal ruler. Historians have asked whether Xenophon's portrait of Cyrus was accurate or if Xenophon imbued Cyrus with events from Xenophon's own life. There is a consensus that Cyrus's career is best outlined in the Histories of Herodotus.[27] Herodotus contradicts Xenophon at several other points. Herodotus says that Cyrus led a rebellion against his maternal grandfather, Astyages, king of Media, and defeated him, thereafter keeping Astyages in his court for the remainder of his life (Histories 1.130). The Medes were thus "reduced to subjection" (1.130) and became "slaves" (1.129) to the Persians 20 years before the capture of Babylon in 539 BC.

The Cyropaedia relates instead that Astyages died and was succeeded by his son, Cyaxares II, the maternal uncle of Cyrus (1.5.2). In the initial campaign against the Lydians, Babylonians, and their allies, the Medians were led by Cyaxares and the Persians by Cyrus, who was crown prince of the Persians since his father was still alive (4.5.17). Xenophon relates that at this time the Medes were the strongest of the kingdoms that opposed the Babylonians (1.5.2). In the Harran Stele, a document from the court of Nabonidus wrote the same point.[28] In the entry for year 14 or 15 of his reign (542–540 BC), Nabonidus speaks of his enemies as the kings of Egypt, the Medes, and the Arabs. There is no mention of the Persians; according to Herodotus and the current consensus, the Medians had been made "slaves" of the Persians several years previously. An archaeological bas-reliefs in the stairway at Persepolis shows no distinction in official status between the Persian and Median. Olmstead nevertheless wrote, "Medes were honored equally with Persians; they were employed in high office and were chosen to lead Persian armies."[29]

Both Herodotus (1.123,214) and Xenophon (1.5.1,2,4, 8.5.20) present Cyrus as about 40 years old when his forces captured Babylon. In the Nabonidus Chronicle, there is mention of the death of the wife of the king (name not given) within a month after the capture of Babylon.[30] It has been conjectured that this was Cyrus's first wife; Cyropaedia's stated (8.5.19) that Cyaxares II gave his daughter in marriage to Cyrus soon after the fall of the city, with the kingdom of Media as her dowry.

Persians as centaurs

[edit]The Cyropaedia praises the first Persian emperor, Cyrus the Great, and it was through his greatness that the Persian Empire held together. However, following the lead of Leo Strauss, David Johnson suggests that there is a subtle layer to the book in which Xenophon conveys criticism of the Persians, the Spartans, and the Athenians.[31] In section 4.3 of the Cyropaedia, Cyrus wrote his desire to institute cavalry. He wrote that he desires that no Persian kalokagathos ("noble and good man" literally, or simply "noble") ever be seen on foot but always on a horse, so much so that the Persians may actually seem to be centaurs (4.3.22–23).

Xenophon plays upon the post-Persian-war propagandistic paradigm of using mythological imagery to represent the Greco-Persian conflict. Examples of this include the wedding of the Lapiths, Gigantomachy, Trojan War, and Amazonomachy on the Parthenon frieze. Johnson believes that the unstable dichotomy of man and horse found in a centaur is indicative of the unstable alliance of Persian and Mede formulated by Cyrus.[31] He cites the regression of the Persians directly after the death of Cyrus as the result of this instability, a union made possible only through Cyrus.[31]

Against empire

[edit]

The strength of Cyrus in holding the empire together is praiseworthy, according to Xenophon. However, the empire began to decline upon the death of Cyrus. By this example, Xenophon sought to show that empires lacked stability and could only be maintained by a person of remarkable prowess, such as Cyrus.[31]

Xenophon displays Cyrus as a lofty, temperate man. He is depicted as not subject to the foibles of others. He used the example of the Persians to decry the attempts at empire made by Athens and Sparta.[32] Having written the Cyropaedia after the downfall of Athens in the Peloponnesian War, this work criticizes the Greek attempts at empire and "monarchy".

Against democracy

[edit]Another passage that Johnson cites as criticism of monarchy and empire concerns the devaluation of the homotīmoi ("equal", or "same honours", i.e., "peers"). Homotīmoi were highly educated and thus became the core of the soldiers as heavy infantry. Their band (1000 when Cyrus fought the Assyrians) shared equally in the spoils of war.[31] However, in the face of overwhelming numbers against the Assyrians, Cyrus armed the commoners with similar arms instead of their normal light ranged armament (Cyropaedia 2.1.9).

Argument ensued as to how the spoils would now be split, and Cyrus enforced a meritocracy. Many homotīmoi found this unfair because their military training was no better than the commoners, only their education, and hand-to-hand combat was less a matter of skill than strength and bravery. As Johnson asserts, this passage decries imperial meritocracy and corruption, for the homotīmoi now had to ingratiate themselves to the emperor for positions and honours;[31] from this point, they were referred to as entīmoi, no longer of the "same honours" but having to be "in" to get the honour.

Constitution of the Spartans

[edit]The Spartans wrote nothing about themselves, or if they did it, it is lost. Xenophon, in the Constitution of the Spartans, wrote:

It occurred to me one day that Sparta, though among the most thinly populated of states, was evidently the most powerful and most celebrated city in Greece; and I fell to wondering how this could have happened. But when I considered the institutions of the Spartans, I wondered no longer.[33]

Xenophon goes on to describe in detail the main aspects of Laconia.

Old Oligarch

[edit]A short treatise on the Constitution of the Athenians exists that was once thought to be written by Xenophon was probably written when Xenophon was about five years old. The author, often called in English the "Old Oligarch" or Pseudo-Xenophon,[34] detests the democracy of Athens and the poorer classes, but he argues that the Periclean institutions are well designed for their deplorable purposes.

Socratic works and dialogues

[edit]

Xenophon's works include a selection of Socratic dialogues; these writings are preserved. Except for the dialogues of Plato, they are the only surviving representatives of the genre of Socratic dialogue. These works include Xenophon's Apology, Memorabilia, Symposium, and Oeconomicus. The Symposium outlines the character of Socrates as he and his companions discuss what attributes they take pride in. One of the main plots of the Symposium is about the type of loving relationship (noble or base) a rich aristocrat will be able to establish with a young boy (present at the banquet alongside his own father). In Oeconomicus, Socrates explains how to manage a household. Both the Apology and the Memorabilia defend Socrates' character and teachings. The former is set during the trial of Socrates, while the latter explains his moral principles and that he was not a corrupter of the youth.

Although Xenophon claims to have been present at the Symposium, he was only a young boy at the date on which he proposes. Xenophon was not present at the trial of Socrates, having been on campaign in Anatolia and Mesopotamia. It seems that Xenophon wrote his Apology and Memorabilia as defences of his former teacher and to further the philosophic project, not to present a literal transcript of Socrates' response to the historical charges incurred.[35]

Relationship with Socrates

[edit]Xenophon was a student of Socrates. In his Lives of Eminent Philosophers, the Greek biographer Diogenes Laërtius (who writes many centuries later) reports how Xenophon met Socrates. "They say that Socrates met [Xenophon] in a narrow lane, and put his stick across it and prevented him from passing by, asking him where all kinds of necessary things were sold. And when he had answered him, he asked him again where men were made good and virtuous. And as he did not know, he said, 'Follow me, then, and learn.' And from this time forth, Xenophon became a follower of Socrates."[36] Diogenes Laërtius also relates an incident "when in the battle of Delium Xenophon had fallen from his horse" and Socrates reputedly "stepped in and saved his life."[37]

Both Plato and Xenophon wrote Apology concerning the death of Socrates. Xenophon and Plato seem to be concerned with the failures of Socrates to defend himself. Xenophon asserts that Socrates dealt with his prosecution in an exceedingly arrogant manner, or at least was perceived to have spoken arrogantly. Conversely, while not omitting it completely, Plato worked to temper that arrogance in his own Apology. Xenophon framed Socrates' defense, which both men admit was not prepared at all, not as a failure to argue, but as striving for death even in the light of unconvincing charges. As Danzig interprets it, convincing the jury to condemn him even on unconvincing charges would be a rhetorical challenge worthy of the great persuader.[35] By contrast, Plato argued that Socrates was attempting to demonstrate a higher moral standard and teach a lesson.[35]

Modern reception

[edit]

Xenophon's lessons on leadership have been reconsidered for their modern-day value.[38] The Cyropaedia, in outlining Cyrus as an ideal leader, is the work that O'Flannery suggests be used as a guide or example for those striving to be leaders. The linking of moral code and education is a quality subscribed to Cyrus that O'Flannery believes is in line with modern perceptions of leadership.[38]

List of works

[edit]

Xenophon's entire classical corpus is extant.[39] The following is a list of his works.

Historical and biographical works

[edit]- Anabasis (also: The Persian Expedition or The March Up Country or The Expedition of Cyrus): Provides an early life biography of Xenophon. Anabasis was used as a field guide by Alexander the Great during the early phases of his expedition into the Achaemenid Empire.

- Cyropaedia (also: The Education of Cyrus): Sometimes seen as the archetype of the European "mirror of princes" genre.

- Hellenica: His Hellenica is a major primary source for events in Greece from 411 to 362 BC, and is the continuation of the History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, going so far as to begin with the phrase "Following these events...". The Hellenica recounts the last seven years of the Peloponnesian War, as well as its aftermath, and is a detailed and direct account (however partial to Sparta) of the history of Greece until 362 BC.

- Agesilaus: The biography of Agesilaus II, king of Sparta and companion of Xenophon.

- Polity of the Lacedaemonians: Xenophon's history and description of the Spartan government and institutions.

Socratic works and dialogues

[edit]Defences of Socrates

[edit]- Memorabilia: Collection of Socratic dialogues serving as a defense of Socrates outside of court.

- Apology: Xenophon's defence of Socrates in court.

Other Socratic dialogues

[edit]- Oeconomicus: Socratic dialogue of a different sort, pertaining to household management and agriculture.

- Symposium: Symposic literature in which Socrates and his companions discuss what they take pride in with respect to themselves.

Tyrants

[edit]- Hiero: Dialogue about happiness between Hiero, the tyrant of Syracuse, and the lyric poet Simonides of Ceos.

Short treatises

[edit]These works were probably written by Xenophon when he was living in Scillus. His days were likely spent in relative leisure here, and he wrote these treatises about the sorts of activities he spent time on.

- On Horsemanship: Treatise on how to break, train, and care for horses.

- Hipparchikos: Outlines the duties of a cavalry officer.

- Hunting with Dogs: Treatise on the proper methods of hunting with dogs and the advantages of hunting.

- Ways and Means: Describes how Athens should deal with financial and economic crisis.

Spuria

[edit]- Constitution of the Athenians: Describes and criticizes Athenian democracy; now thought not to be by Xenophon.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Strassler et al., xvii (Archived 20 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ a b Lu, Houliang (2014). Xenophon's Theory of Moral Education. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 155. ISBN 978-1443871396.

In the case of Xenophon's date of death most modern scholars agree that Xenophon died in his seventies in 355 or 354 B.C.

- ^ "Xenophon". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Theodore Ayrault Dodge, Alexander: A History of the Origin and Growth of the Art of War from Earliest Times to the Battle of Ipsus, B.C. 301, Vol. 1, Houghton Mifflin, 1890, p. 105.

- ^ Gray, Vivienne J., ed. (2010). Xenophon (Oxford Readings in Classical Studies). Xenophon's works and controversies about how to read them: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199216185.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius. Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. Book II, part 6.

- ^ Nadon, Christopher (2001). Xenophon's Prince: Republic and Empire in the Cyropaedia. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520224043.

- ^ "Xenophon". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ ἀνάβασις Archived 25 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Ambler, Wayne (2011). The Anabasis of Cyrus. Translator's preface: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801462368.

- ^ Dodge, pp. 105–106

- ^ Witt, p. 123

- ^ Dodge, p. 107

- ^ Brownson, Carlson L. (Carleton Lewis) (1886). Xenophon;. Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press.

- ^ Witt, p. 136

- ^ Dodge, p. 109

- ^ Witt, p. 166

- ^ Witt, pp. 175–176

- ^ Witt, pp. 181–184

- ^ Dodge, Theodore Ayrault. Great Captains: A Course of Six Lectures on the Art of War. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York: 1890. p. 7

- ^ Hellenica III, 1

- ^ a b Hellenica III, 2

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius. Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. Book II, part 5.

- ^ "Pausanias, Description of Greece, Elis 1, chapter 6". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Pangle, "Socrates Founding Political Philosophy in Xenophon's Economist, Symposium, and Apology", ISBN 978-0226642475

- ^ Ashley Cooper, Maurice (1803). Cyropædia; or, The institution of Cyrus, . London. Printed by J. Swan for Vernor and Hood [etc.]

- ^ Steven W. Hirsch, "1001 Iranian Nights: History and Fiction in Xenophon's Cyropaedia", in The Greek Historians: Literature and History: Papers Presented to A. E. Raubitschek. Saratoga CA: ANMA Libr, 1985, p. 80.

- ^ Pritchard, James B., ed. (1969). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (3rd ed.). Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press. pp. 562–63.

- ^ Olmsted, A. T. (1948). History of the Persian Empire. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. p. 37.

- ^ Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts, p. 306b.

- ^ a b c d e f Johnson, D. M. 2005. "Persians as Centaurs in Xenophon's ‘Cyropaedia'", Transactions of the American Philological Association. Vol 135, No. 1, pp. 177–207.

- ^ Johnson, D. M. 2005. "Persians as Centaurs in Xenophon's ‘Cyropaedia'", Transactions of the American Philological Association. Vol 135, No. 1, pp. 177–207

- ^ "Xenophon, Constitution of the Lacedaimonians, chapter 1, section 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Norwood 1930, p. 373.

- ^ a b c Danzig, Gabriel. 2003. "Apologizing for Socrates: Plato and Xenophon on Socrates' Behavior in Court." Transactions of the American Philological Association. Vol. 133, No. 2, pp. 281–321.

- ^ Laertius, Diogenes. "thegreatthinkers.org". Great Thinkers. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Laertius, Diogenes. "Socrates". Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers.

- ^ a b O'Flannery, Jennifer. 2003. "Xenophon's (The Education of Cyrus) and Ideal Leadership Lessons for Modern Public Administration." Public Administration Quarterly. Vol. 27, No. 1/2, pp. 41–64.

- ^ See for example the Landmark edition of Xenophon's Hellenika. In the preface Strassler writes (xxi), "Fifteen works were transmitted through antiquity under Xenophon's name, and fortunately all fifteen have come down to us".

Bibliography

[edit]- Bradley, Patrick J. "Irony and the Narrator in Xenophon's Anabasis", in Xenophon. Ed. Vivienne J. Gray. Oxford University Press, 2010 (ISBN 978-0199216185.

- Brennan, Shane. Xenophon's Anabasis: A Socratic History. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022 (ISBN 978-1474489881)

- Anderson, J.K. Xenophon. London: Duckworth, 2001 (paperback, ISBN 185399619X).

- Buzzetti, Eric. Xenophon the Socratic Prince: The Argument of the Anabasis of Cyrus. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014 (hardcover, ISBN 978-1137333308).

- Xénophon et Socrate: actes du colloque d'Aix-en-Provence (6–9 novembre 2003). Ed. par Narcy, Michel and Alonso Tordesillas. Paris: J. Vrin, 2008. 322 p. Bibliothèque d'histoire de la philosophie. Nouvelle série, ISBN 978-2711619870.

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault. “Alexander. A History of the Origin and Growth of the Art of War, from the Earliest Times to the Battle of Ipsus, b.c. 301”. Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin Company: 1890. pp. 105–112

- Dillery, John. Xenophon and the History of His Times. London; New York: Routledge, 1995 (hardcover, ISBN 041509139X).

- Evans, R.L.S. "Xenophon" in The Dictionary of Literary Biography: Greek Writers. Ed.Ward Briggs. Vol. 176, 1997.

- Gray, V.J. The Years 375 to 371 BC: A Case Study in the Reliability of Diodorus Siculus and Xenophon, The Classical Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 2. (1980), pp. 306–326.

- Gray, V. J., Xenophon on Government. Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics. Cambridge University Press (2007).

- Higgins, William Edward. Xenophon the Athenian: The Problem of the Individual and the Society of the "Polis". Albany: State University of New York Press, 1977 (hardcover, ISBN 087395369X).

- Hirsch, Steven W. The Friendship of the Barbarians: Xenophon and the Persian Empire. Hanover; London: University Press of New England, 1985 (hardcover, ISBN 978-0874513226).

- Hutchinson, Godfrey. Xenophon and the Art of Command. London: Greenhill Books, 2000 (hardcover, ISBN 1853674176).

- The Long March: Xenophon and the Ten Thousand, edited by Robin Lane Fox. New Heaven, Connecticut; London: Yale University Press, 2004 (hardcover, ISBN 0300104030).

- Kierkegaard, Søren A. The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992 (ISBN 978-0691020723)

- Moles, J.L. "Xenophon and Callicratidas", The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 114. (1994), pp. 70–84.

- Nadon, Christopher. Xenophon's Prince: Republic and Empire in the "Cyropaedia". Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press, 2001 (hardcover, ISBN 0520224043).

- Norwood, Gilbert (1930). "The Earliest Prose Work of Athens". The Classical Journal. 25 (5).

- Nussbaum, G.B. The Ten Thousand: A Study in Social Organization and Action in Xenophon's "Anabasis". (Social and Economic Commentaries on Classical Texts; 4). Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1967.

- Phillips, A.A & Willcock M.M. Xenophon & Arrian On Hunting With Hounds, contains Cynegeticus original texts, translations & commentary. Warminster: Aris & Phillips Ltd., 1999 (paperback ISBN 0856687065).

- Pomeroy, Sarah, Xenophon, Oeconomicus: A social and historical commentary, with a new English translation. Clarendon Press, 1994.

- Rahn, Peter J. "Xenophon's Developing Historiography", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 102. (1971), pp. 497–508.

- Rood, Tim. The Sea! The Sea!: The Shout of the Ten Thousand in the Modern Imagination. London: Duckworth Publishing, 2004 (paperback, ISBN 0715633082); Woodstock, New York; New York: The Overlook Press, (hardcover, ISBN 1585676640); 2006 (paperback, ISBN 1585678244).

- Strassler, Robert B., John Marincola, & David Thomas. The Landmark Xenophon's Hellenika. New York: Pantheon Books, 2009 (hardcover, ISBN 978-0375422553).

- Strauss, Leo. Xenophon's Socrates. Ithaca, New York; London: Cornell University Press, 1972 (hardcover, ISBN 0801407125); South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustines Press, 2004 (paperback, ISBN 1587319667).

- Stronk, J.P. The Ten Thousand in Thrace: An Archaeological and Historical Commentary on Xenophon's Anabasis, Books VI, iii–vi – VIII (Amsterdam Classical Monographs; 2). Amsterdam: J.C. Gieben, 1995 (hardcover, ISBN 905063396X).

- Usher, S. "Xenophon, Critias and Theramenes", The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 88. (1968), pp. 128–135.

- Witt, Prof. C. “The Retreat of the Ten Thousand”. Longmans, Green and Co.: 1912.

- Waterfield, Robin. Xenophon's Retreat: Greece, Persia and the End of the Golden Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0674023560); London: Faber and Faber, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 978-0571223831).

- Xenophon, Cyropaedia, translated by Walter Miller. Harvard University Press, 1914, ISBN 978-0674990579, (Books 1–5) and ISBN 978-0674990586, (Books 5–8).

External links

[edit]- "Xenophon". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Graham Oliver's Xenophon Homepage

- Xenophon's Education of Cyrus (Cyropaedia) Web directory

- Famous Quotes by Xenophon

- Sanders (1903) Ph D Thesis on The Cynegeticus

- Xenophon at Somni

- Online works

- Works by Xenophon at Perseus Digital Library

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.- Links to English translations of Xenophon's works

- Leo Strauss' Seminar Transcripts on Xenophon (1962, 1966); and an audio recording of the entire course on Xenophon's Oeconomicus (1969) are available for reading, listening or download.

- Works by Xenophon at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Xenophon at the Internet Archive

- Works by Xenophon at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 430s BC births

- 354 BC deaths

- 4th-century BC Greek people

- 4th-century BC historians

- 4th-century BC writers

- Ancient Athenian generals

- Ancient Athenian historians

- Ancient Athenian philosophers

- Ancient Greek generals

- Ancient Greek historians

- Ancient Greek mercenaries

- Ancient Greek military writers

- Ancient Greek political philosophers

- Attic Greek writers

- Classical-era Greek historians

- Classical horsemanship

- Greco-Persian Wars

- Military personnel of the Achaemenid Empire

- Ostracized Athenians

- Pupils of Socrates

- Social philosophers

- Writers on horsemanship

- Memoirists

- Ten Thousand-ancient mercenaries